This paper discusses one particular complex external historical figure in the history of the shaping of the New Testament canon: Marcion of Sinope (c. AD 85–160) and his influence. Did Marcion create the idea to form a New Testament canon?

This is principally a historical exploration; however, there are numerous theological aspects that must be reflected upon and critiqued in order to have a functional and accurate understanding of Marcion’s role.

Factors and Dynamics

The history of the biblical canon is home to many overlapping complexities. The study of these aspects reveals the richness of canonical development, especially when one differentiates between the histories of the Hebrew and the Christian canons respectively.[1]

Canonical development can be studied from a theological vantage point, taking into account theological motives for the collection of books; however, such theological motivations must also be placed in a historical framework.[2] On this point, note Nicolaas Appel: “the mystery of Scripture and faith of the Christian community go hand in hand. The canon of Scripture and human history cannot be separated.”[3] The development of the canon combines theology and history, consequently, one’s approach must of necessity intertwine these two factors.

These dynamics of theology and history may be described as internal and external factors. Church historian, Everett Ferguson, differentiates between these somewhat intuitive concepts:

The conviction of a new saving work of God in Christ, its proclamation by apostles and evangelists, and the revelation of its meaning and application by prophets and teachers, led naturally to the writing of these messages and their acceptance as authoritative in parallel with the books already regarded as divine. External factors did not determine that there would be a New Testament canon nor dictate its contents. However, external factors influenced the process of definition and likely hastened that process.[4]

(Ferguson, “Factors”)

The external factors are largely seen as “debates in the post-apostolic church” where the matter was how to find the “voice of revelation and authentic Christianity” in the midst of doctrinal controversy. Thus, as a matter of course, external factors helped in the “definition of the boundaries of right belief”–orthodoxy.[5]

Marcion’s influence in the church came about for several reasons and is not limited to his gnostic tendencies. Marcion rejected a large number of canonical works: the entire Old Testament, and all of the New Testament canon except for eleven edited documents (Luke, Romans-2 Thessalonians, Philemon). In essence, in creating a list of authoritative books it may be said that he created a canon, though likely this was a list of edited documents that represented his particular view of Christianity. Historically, Marcion’s list is considered the earliest “canonical list” of the new Christian community.[6] Consequently, a discussion has arisen, questioning if Marcion is “the father” of canonical development.

Marcion’s early second-century A.D. formation of a collection of authoritative documents affirming Christian faith is chronologically significant.[7] Until Marcion’s time, the post-apostolic church does not appear to have outlined a collection, consequently, some scholars believe that Marcion initiated the contours of the New Testament canon. Others believe a better explanation is that Marcion merely sped along a pre-existing process. After all, the theological principle of the canon was well understood among Jewish Christians, having a canonical set of books of their own.[8]

Additionally, the apostles’ oral preaching and written instruction to the churches demonstrated their authority.[9] But what shall be here presented is that from a practical point of view, a fluid form of a “canon” existed in the late first century and early second century, even if quantitatively incomplete.[10] If this can be shown, then Marcion is not the creator of the idea of the Christian canon.[11]

Marcion of Sinope (c. AD 85–160)

Background

One cannot understand Marcion’s role in the formation of the canon without consideration of his life and beliefs. Church historian, Philip Schaff, remarks that Marcion was raised in a Christian tradition in Pontus near the Black Sea; in fact, his father was a bishop of Sinope in Pontus.[12] Despite being zealous and sacrificial, “due to some heretical opinions,” Schaff observes, he “was excommunicated by his own father, probably on account of his heretical opinions and contempt for authority.”[13]

After leaving Pontus, Marcion traveled to Rome (A.D. 140–155), joined Cerdo (a Syrian Gnostic), and popularized his views among the various Italian churches during his preaching tours.[14] It was during this period that Marcion made a name for himself in Christian history, as he advanced his Christian-based Gnostic teaching, and edited a corpus of New Testament works. Bruce Metzger notes that Marcion was eventually excommunicated in Rome for his heretical views.[15] This move only solidified Marcion as a significant heretic of his time, so much so, that Edwin Yamauchi ranks him among the top eight Gnostic heretics of the second and third centuries.[16]

A Gnostic Heretic

Marcion is “known” as a Gnostic heretic of the ancient church, but one must be cautious regarding such labels. Harold Brown provides one particular strong reason why. Brown distinguishes between the gnostic movement –“a widespread religious phenomenon of the Hellenistic world at the beginning of the Christian Era”– and the Christian manifestation of this movement designated Gnosticism (lowercase g, versus uppercase G).[17] Brown’s distinction is noteworthy as the Christian gnostic movement, Gnosticism, was “a response to the widespread desire to understand the mystery of being: it offered detailed, secret knowledge of the whole order of reality, claiming to know and to be able to explain things of which ordinary, simple Christian faith was entirely ignorant.”[18]

As a fundamental aspect of this belief, existence was viewed as “a constant interplay between two fundamental principles, such as spirit and matter, soul and body, good and evil.”[19] But the gnostic worldview and its Christian mutation are not monolithic.

Edwin Yamauchi notes that Marcion “was not a typical Gnostic. He stressed the need of faith rather than gnosis. But his attitude toward the Old Testament was typically Gnostic.”[20] Thus, Marcion was not always fully aligned with other Gnostic ideas. Despite this distinction, it is noteworthy to see how Irenaeus (b. AD 130), a contemporary critic of Marcion, describes Marcion’s influence and placement among the gnostics in the church.

Irenaeus places Marcion within the stream of Cerdo, a second-century gnostic teacher:

Marcion of Pontus succeeded him [Cerdo], and developed his doctrine. In so doing, he advanced the most daring blasphemy against Him who is proclaimed as God by the law and the prophets, declaring Him to be the author of evils, to take delight in war, to be infirm of purpose, and even to be contrary to Himself.[21]

(Against Heresies 1:27:2)

Irenaeus affirms a connection between Cerdo and Marcion flavored with “passing of the heretical torch” overtones. Justin Martyr (c. AD 100–165) regarded him as one who “the devils put forward” (1 Apology 58); moreover, Irenaeus reports that, “Polycarp himself replied to Marcion, who met him on one occasion and said, ‘Dost thou know me?’ ‘I do know thee, the first-born of Satan’” (Against Heresies 3.3.4).

Ferguson suggests patristic descriptions like these of Marcion are rather important because it demonstrates how the early church remembered him; he was a heretic, not a benchmark in canonical development.[22]

Assessing Marcion’s Theology

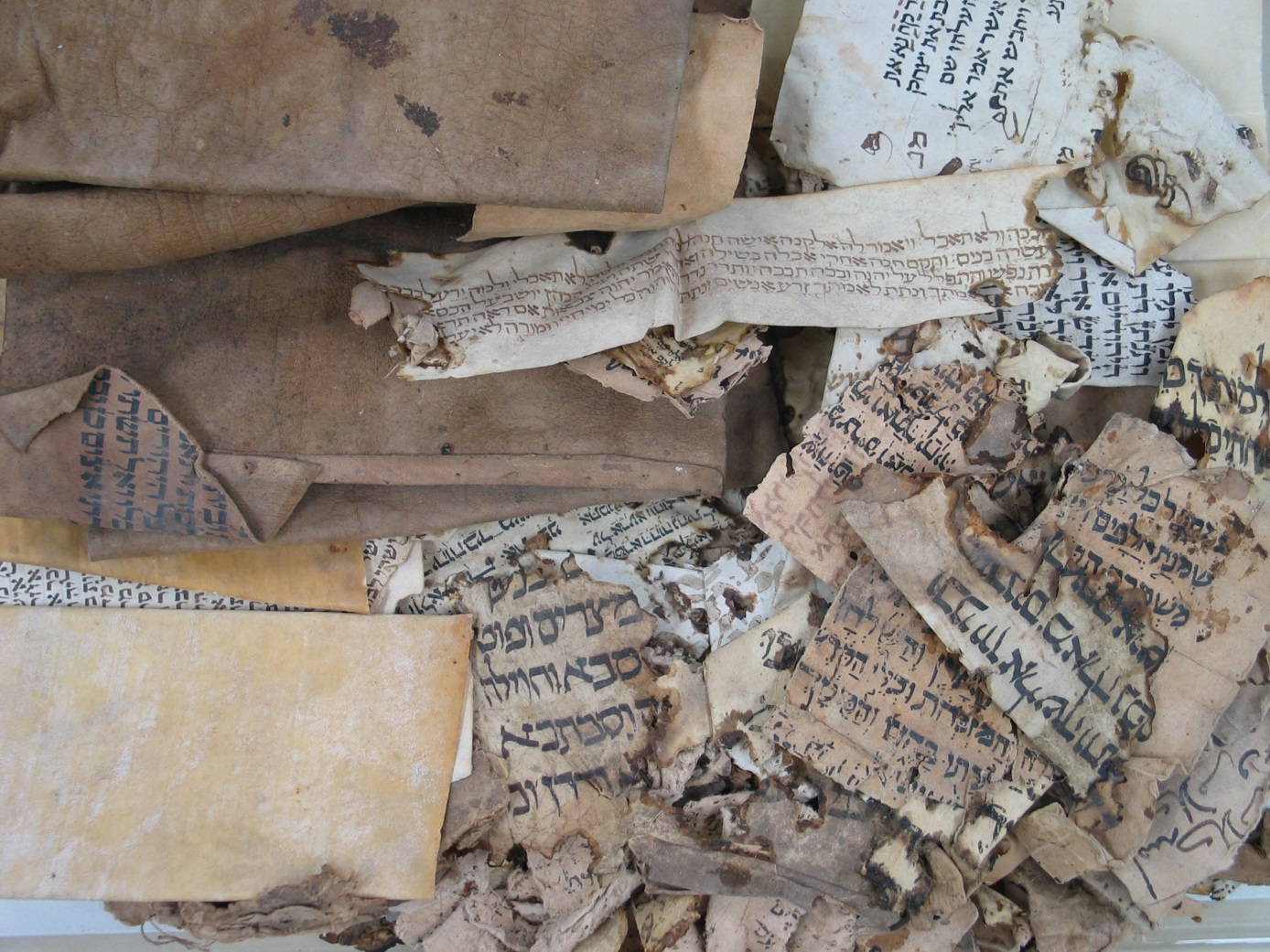

Unfortunately, Marcion’s work does not exist in any extant manuscript. Outside of his prologues found in Latin New Testament texts, his views are only extant by references in the works of others.[23] Marcion’s only known work is called Antitheses (“Contradictions”), which served in an introductory capacity to his collection of documents.[24] It is not all sure what exactly was in Antitheses; consequently, as Bruce Metzger words it, “we have to content ourselves with deducing its contents from notices contained in the writings of opponents – particularly in Tertullian’s five volumes written against Marcion.”[25] Extant patristic authors who paid particular attention to Marcion are Justin Martyr (1 Apology), Irenaeus (Against Heresies), and Hippolytus (Refutation of All Heresies).

Christian historians are left to boil down Marcion’s beliefs. Schaff suggested three points at the maximum.[26] John Barton, however, reduces his theology in a two-fold manner.[27]

In Schaff’s summary of Marcion’s religious views, he acknowledges his Gnostic influences and beliefs but qualifies that Marcion was also a firm believer in Christianity as the only true religion. Still, it must be reminded that it was Marcion’s version of Christianity which he thought was the only true religion. Schaff writes:

Marcion supposed two or three primal forces (archaí): the good or gracious God (theòs agathós), whom Christ first made known; the evil matter (húlē), ruled by the devil, to which heathenism belongs; and the righteous world-maker (dēmiourgòs díkaios), who is the finite, imperfect, angry Jehovah of the Jews.[28]

(Schaff, History of the Christian Church 2.484).

Marcion, though, rejected the “pagan emanation theory, the secret tradition, and the allegorical interpretation of the Gnostics,” the typical gnostic tenets of Pleroma, Aeons, Dynameis, Syzygies, and the suffering Sophia.[29] These are the various ways in which Marcion did not stand in the same grouping as other Gnostics of his era. Yet, in short, on Schaff’s evaluation, Marcion believed in the good God of Jesus, an evil material universe, and that the Old Testament God was a finite imperfect world-marker. These are clearly on the grid of Gnosticism.

John Barton argues compellingly, however, that Marcion was in error in two large ways, each of which revealed how he viewed the Bible. The first is found in how he interpreted the God of the Old Testament:

[Marcion] had rejected the Old Testament as having any authority for Christians, arguing that the God of whom it spoke, the God of the Jews, was entirely different from the Christian God who had revealed himself in Jesus as the Savior of the world; indeed, it was from the evil creator-god of the Old Testament that Jesus had delivered his followers.[30]

John Barton “Marcion”

Justin Martyr similarly declares, Marcion teaches

his disciples to believe in some other god greater than the Creator. And he, […], has caused many of every nation to speak blasphemies, and to deny that God is the maker of this universe, and to assert that some other being, greater than He, has done greater works.[31]

(First Apology 26)

The second problem Marcion was in his truncation and editorial work on his collection of New Testament documents.[32] Irenaeus wrote:

[Marcion] mutilates the Gospel which is according to Luke, removing all that is written respecting the generation of the Lord, and setting aside a great deal of the teaching of the Lord, in which the Lord is recorded as most dearly confessing that the Maker of this universe is His Father. […]. In like manner, too, he dismembered the Epistles of Paul, removing all that is said by the apostle respecting that God who made the world.[33]

(Against Heresies 1:27:2)

As Tertullian writes, “Marcion expressly and openly used the knife, rather than the pen,” demonstrating that Marcion had a theological purpose for his “final cut.” Such “excisions of the Scriptures” was made, Tertullian explains, “to suit his own subject matter” (Prescription Against Heresies 38).[34]

In Barton’s view, Marcion rejected the Old Testament and accepted Jesus Christ and Christianity apart from Hebrew influences. He did not reject the notion that the God of the Old Testament existed. In fact, he firmly believed that he did. “The problem,” as Barton observes, “was that his creation was evil, and he himself therefore was a malign being; it was precisely the role of Jesus and of the Unknown God now revealed in him, to deliver humankind from the malice of the evil Creator.”[35] The rejection of the Old Testament must be qualified because Marcion accepted its divine origin, only that it is the result of an evil god.[36]

Marcion’s so-called “canon” was, in essence, a product of his version of the Gospel message, namely that “the good news of Jesus and the salvation brought by him” showed that the Old Testament was “the utterances of an evil being.”[37] Yet, his action to establish what he believed to be the authentic “gospel” also “cut” a line in the sand. Retrospectively, his actions affected the history of the Christian canon.

Marcion’s Collection and the Canon

Marcion’s Collection

F. F. Bruce observed that Marcion became the “first person known to us who published a fixed collection of what we should call the New Testament books.”[38] Whether or not others had done so before Marcion is irrelevant, Bruce asserts, as there is no knowledge of any other list.[39]

Marcion’s Antithesis was a treatise on the incompatibility of “law and gospel, of the Creator-Judge of the Old Testament and the merciful Father of the New Testament (who had nothing to do with either creation or judgment).”[40] This led to his bipartite collection (Gospel and Paul). As framed by Tertullian, Marcion composed of a mutilated version of Luke and “dismembered” parts of Paul’s epistles, which were all subject to his editorial “knife.”[41] This collection appeared and began to be circulated around A.D. 140 at the earliest, and possibly A.D. 150 due to a late edition of Luke.[42]

Marcion’s collection of the Gospel and Paul included an edited Gospel of Luke and a reduced Pauline corpus composed of Romans, 1–2 Corinthians, Galatians, Laodiceans (i.e., Ephesians), Philippians, Colossians, 1–2 Thessalonians, and Philemon. This was Marcion’s “canon.” But what is canon?

What is Canon?

The word “canon” (kanōn) has three basic meanings which play, as Harry Gamble observed, some role in the conception of the canonization of Scripture.[43] Deriving from the literal origin of being a reed of bulrush or papyrus, the Greek word kanōn came to denote for the craftsman a “measuring rod,” a “rule,” or simply put “a tool for measurement or alignment” hence “straight rod.”[44] The literal meaning gave way to metaphorical usage in keeping with the concept of standardization, thus canon became also synonymous with “an ideal standard, a firm criterion against which something could be evaluated and judged.”[45] Canon also came to mean “a list” or “a catalog” which seems to have been based on the calibration marks on the reed stick.[46]

All these uses of the canon have also found their way into the broader limits of the liberal arts for identifying unparalleled standards, but when it applies to sacred literature “canon denotes a list or collection of authoritative books.”[47] Canonical Christian literature as Scripture means these works are “the rule of faith” (regula fidei) and “the rule of truth” (regula veritatis); and as such, they are governing normative standards of apostolic faith with inherent value.[48]

It would be a mistake to think of a book that had to wait to be on a list to be regarded as canonical, or representative of faith and truth. As will be noted, canonicity is a qualitative threshold, not a quantitative one. It would be a mistake to think that simply on the grounds of Marcion’s list there were no other books recognized as possessing canonical status.

The Emerging Qualitative Canon

There is sufficient evidence to demonstrate that a fluid form of a canon existed–albeit quantitatively incomplete–in the late first century and the early second century.[49] Two passages that are particularly noteworthy are 2 Peter 3:15–16 and 2 Timothy 4:11–13, for they demonstrate that Paul’s letters were already being collected in the first century. Even if a pseudepigraphic near-second-century view of these epistles is correct, which is still a matter of dispute, the documents are still primary witnesses to the collection process of New Testament documents during this era.[50]

Factors Hindering the Formation of the Canon

Before evaluating what 2 Timothy and 2 Peter bring to the discussion of Marcion’s role in the formation of the New Testament canon, it appears vitally important to remember that there were various factors that hampered the collection process.

Dowell Flatt, Bible Professor of New Testament studies (Freed-Hardeman University), notes that there are at least seven important factors that hampered the canonization process of the New Testament.[51] First, the Old Testament was employed authoritatively and interpreted Christologically by the early church, consequently, “it did not immediately appear that another set of books would be needed.”

Second, the early church was still under the shadow of the Lord’s presence, and many of them would feel “no need for a written account of his life.”

Third, eyewitnesses (apostles and close disciples) to the Lord’s life and work were still alive (1 Cor 15:6); consequently, this adds to the strength of the second point.

Fourth, oral tradition was a vital element in the early Jewish make-up of the early church, and “as strange as it might sound to modern ears, many Jewish teachers did not commit their teachings to writing.” Oral tradition was important even around 130 A.D. for Papias felt that “the word of a living, surviving voice” was more important than “information from books.”[52] Some of the importance placed upon oral tradition is due to the expense of books, and illiteracy; and that Jesus did not write or command his disciples to write a word.[53]

Fifth, the nature of many apostolic writings was letters, not literary works, so is it understandable that “such writings” as the letters “were slow to be fully recognized as Scripture.” Sixth, the belief in a realized eschatology in the first century had “some influence” in hampering of the canonization process.

Seventh, the divinely inspired would speak a prophetic word, and while this was available the church was in no need of a written record per se (Flatt 139). Kurt Aland observes the second-century church, living beyond this blessing, “began to carefully distinguish between the apostolic past and the present.”[54]

King McCarver adds an eighth factor. There was no “ecclesiastical organization” that “composed or established the canon,” but instead the slow reception of these works at various intervals, across a large geographical region, of the early church was the context of the early sifting process before the councils.[55]

Evidence from 2 Peter and 2 Timothy

If Peter is the author of 2 Peter, which the author believes there is sufficient evidence to suggest he is, then the 2 Peter would be dated in the early 60s of the first century (before his traditional martyrdom in A.D. 65). Should 2 Peter be late, the epistle is typically dated to the end of the first century. This is principally due to the strong verbal allusions in the Apostolic Fathers, particularly in 1 Clement (A.D. 95–97) and 2 Clement (A.D. 98–100).[56] The latest reasonable date for 2 Peter is A.D. 80–90, generally argued for by Richard Bauckham, who views the letters as non-Petrine.[57]

In a similar fashion, if Paul is the author of 2 Timothy then it would generally be accepted to be also written in the first century (A.D. 55-60s), before his martyrdom, traditionally under Nero (A.D. 68). However, as W. Kümmel asserts, being a proponent of pseudepigraphic authorship of the pastorals (1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus), if 2 Timothy is not Pauline then it was probably penned around the “beginning of the second century.[58]

With these relevant items in mind, attention is now given to 2 Timothy and 2 Peter.

2 Peter 3:14–17

2 Peter 3:14–17 is the capstone of a moral argument set forth in the epistolē, rising from both apostolic theology and eschatology. The text may be translated as follows:

[14] Therefore, loved ones, since you wait for these things be eager to be found by him as spotless ones and blameless ones in peace; [15] and consider the patience of our Lord as salvation, just as also our beloved brother Paul (according to the wisdom entrusted to him) wrote to you,[16] as also by all [his] letters addressing these things in them, in which it is hard to understand some things, which those who are ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction as also the remaining Scriptures. [17] You therefore, loved ones, knowing in advance, be on your guard, in order that you may not be carried away from [your] firm footing by the error of lawless people. (Author's Translation)

Of particular interest here is the vocabulary employed in verses 15–16, for it is very clear that the author of 2 Peter is employing the authoritative weight of the Apostle Paul and the group of his letters (pásais epistolaís, “all [his] letters”) to support his argument. Moreover, the false teachers, characterized as being “ignorant” (amatheís) and “unstable” (astēriktoi), are twisting (strebloúsin) Paul’s words and the “remaining Scriptures” (tàs loipàs graphàs) to their “destruction” (apōleian).

The language itself bears very close similarities with canonical language; basically, language which recognizes normative revelation.[59] Conceptionally, the author of 2 Peter is appealing to an inspired holy prophet (i.e., Paul 3:15; cf. 1:20–21; 3:2), the normative Scriptures of the Hebrews (3:5–6), and himself implicitly as one who can identify the “prophetic word” (1.19). Despite one’s views towards the authorship of 2 Peter this simple observation must not be overlooked. Neyrey, who questions the validity of the argument here, recognizes that this may be a claim of “legitimacy […] There is only one tradition of teaching of God’s judgment and Jesus’ parousia.” This has the double effect of authenticating 2 Peter’s argument, while “automatically discrediting” the false teachers.[60]

Richard Bauckham likewise agrees that the author, whoever he is, “wishes to point out that his own teaching (specifically in 3:14–15a) is in harmony with Paul’s because Paul was an important authority for his readers.”[61] The appeal to a normative standard is definitely a necessity in order to demonstrate the validity of the argument. Is that not a canonical concept?

If the author of 2 Peter is employing normative, or standard theological argumentation based upon authoritative figures (Paul and the Old Testament) the implication is that the false teachers are not. Even if they are, the false teachers are so misconstruing Paul and the Old Testament’s affirmations that they are “torturing” them, to the point of making them appear as if they teach something that they do not (strebloúsin); thus, the audience is to understand that there is a normative standard.[62]

The language of the passage is again revealing. Paul is regarded as one who was endowed with wisdom (dotheísan autō sophían), which is a natural allusion to his direct reception of revelation elsewhere synonymously described (1 Cor 2:11–13 lambánō; Gal 1:12–17 apokalúpseōs).[63] The Pauline letters, however many are referred to, are saturated by this wisdom, but are subject to the false teacher’s interpretive methods, and since they are torturing them this behavior leads to their own destruction.

It seems that this destruction stems from the fact that Paul’s letters and tàs loipàs graphàs (“the remaining Scriptures”) in some way share the same character.[64] 2 Peter 3.16 connects this torture of tàs loipàs graphàs to their destruction as well, meaning that the same kind of punishment awaiting those who distort the meaning of Paul’s letters is awaiting those who twist the “rest of the Scriptures.”[65] This refers to the Old Testament Scriptures[66]; even Bauckham, who is opposed to Petrine authorship, concedes at the least that “it would make no sense to take graphàs in the nontechnical sense of ‘writings’; the definite article requires us to give it its technical sense” though he conceives of other books in the author’s purview.[67] Likewise, Earl J. Richard observes, “that the author means to include in this category the OT Scriptures is obvious, but beyond that it is unclear what Christian works would have been thus labeled.”[68]

From these observations, the proposition is advanced that the author of 2 Peter grounds his argumentation in a reference to accepted authority (tradition, or standard). This authority is threefold: his prophetic office as an apostle; the Apostle Paul’s pásais epistolaís; and the Old Testament. Regardless of the position taken on the authorship question of 2 Peter, the method of argumentation is generally transparent despite some criticism of the validity of the logic within 2 Peter 3:15–16, particularly the admission of the difficulty of Paul’s treatment of some matters.[69] As a document existing before Marcion’s influential era, it poignantly addresses its audience with canonical overtones, demonstrates boldly that Marcion could have not fathered the notion of a New Testament canon, for the Peter appeals to the canon of the Hebrew Bible and a fluid Pauline canon-corpus.

One of the main arguments for 2 Peter 3.15-16 is that there is a Pauline corpus of indefinite size (pásais epistolaís), that both the author and his audience were aware of. Therefore, some consideration of an early Pauline corpus must be given. Some working theory of how Paul’s letters were collected and then circulated must be formulated. It is argued here that the process was both gradual in scope and immediate to Paul. The basis for this belief is grounded in slow circulation among the churches, the typical secretarial duty to make copies, and the arrival and usage of the codex.[70] McCarver observes that the occasional nature of the epistles highlights the point that there was some specificity to a given locale, and consequently as other churches desired copies the “exchange and copying” was gradual.[71]

Randolph Richards, while arguing for an unintentional collection, provides evidence that Paul would have had a copy of any letter in which he employed a secretary.[72] It appears to have been a standard secretarial task to make a copy for a proficient letter writer, and then place it within a codex for safekeeping, which in turn would be a depository for later publication if desired. A codex then became a warehouse for a penman; it would allow the neat copying of helpful phrases or expressions for another letter. Likewise, the secretary would have a copy of the letters for records. Thus, Richards argues that the codex became a practical matter, which ultimately became a pivotal matter in the formation of a Pauline corpus.[73]

2 Timothy 4:11–13

Despite the work being considered pseudonymous by many scholars, 2 Timothy 4:11–13 contributes to this discussion. The text reads:

[11] Luke alone is with me. Get Mark and bring him with you, for he is very useful to me for ministry. [12] Tychicus I have sent to Ephesus. [13] When you come, bring the cloak that I left with Carpus at Troas, also the books, and above all the parchments. (Holy Bible, ESV)

The term “parchments” (membránas) is rather interesting since Paul, according to Richards, “is the only Greek writer of the first century to refer to membránai, a Roman invention.”[74] Parchment codices were used to retain copies of letters for future use to prepare rough drafts of other letters later written to be dispatched.

Interestingly, Richards ponders how this passage is affected if 2 Timothy is non-Pauline, and says that it only affects the explicit claim by Paul, but one can still “contend for Paul’s retaining his copies in a codex notebook solely because of customary practice.”[75] If 2 Timothy is Pauline, it would not be too much longer before Peter would arrive in Rome, if he had not been in Rome already.

Richards speculates fairly that “if Paul retained copies, then in the early 60s there was possibly only one collection in existence – namely, Paul’s personal set of copies.”[76] In connection the Peter and 2 Peter 3:15–16, Richards writes:

The possibility of Peter’s being aware of these [Paul’s person set of letters] or even having read them would be remote unless one postulate, as early traditions do, that Peter and Paul were both in Rome in the early 60s. In such a case, Peter a was in the only place where he could have seen copies of Paul’s letters. It is not unreasonable then to suggest that Peter would not have reviewed what had been written to churches in Asia Minor by Paul before he himself wrote to them, particularly if he was aware that some were confused by Paul’s letters.[77]

Richards, “The Codex and the Early Collection of Paul’s Letters”

Such evidence appears compelling, however, it must be regarded as probable. Despite some of the speculative nature of the reconstruction, Richards’ theory holds up rather strongly with what would have taken place if the traditions of Paul and Peter are correct, and further addresses in a realistic fashion how Peter would have had access to a corpus of Paul’s letters. To say the least, 2 Timothy bolsters the argument made here that there was the beginning of a New Testament document collection earlier than Marcion’s canon.

In light of these points, Simon J. Kistemaker makes a contributing observation that adds bulk to the view that the documents themselves were intrinsically authoritative, but it took time for the church universal to sift through this tremendous body of literature and come to an agreement. Kistemaker argues that the church was accepting a qualitative canon until it accepted a quantitative canon:

“The books themselves, of course, have always been uniquely authoritative from the time of their composition. Therefore, we speak of a qualitative canon in early stages that led to a quantitative canon centuries later. The incipient canon began to exist near the end of the first century. The completed canon was recognized by the Church near the end of the fourth century.[78]

Kistemaker, “The Canon of the New Testament“

Consequently, as has often been maintained, “the church did not create the canon,” but instead, developed from the bottom of the post-apostolic church structure to the top in the various councils to give focused attention to the authenticity of these works.[79]

Assessment

What may be said then regarding Marcion’s role in the formation of the New Testament Canon? Marcion does take a large place in New Testament canonical discussions. C. F. D. Moule poses several possibilities: “was Marcion’s [canon] the first canon, and is the orthodox canon the catholic [i.e. universal] Church’s subsequent reply? Or did Marcion play fast and loose with an already existing canon?” Moule’s answer: “There is at present no absolutely conclusive evidence for the existence of a pre-Marcionite catholic canon. Marcion may have been the catalyst […]. We cannot be certain.”[80]

However, because of the evidence above, it appears that there is more reason to suggest that Marcion was a catalyst to speed along what had been taking a slow time to develop.

Despite Marcion being the “first person known to us who published a fixed collection,”[81] that propelled the church at large to collect an authoritative set of Scripture,[82] the only way, as Ferguson argues, that it can be accepted that Marcion created the canon is possible, is “only by not recognizing the authority that New Testament books already had in the church.”[83] Metzger frames the situation well:

If the authority of the New Testament books resides not in the circumstance of their inclusion within a collection made by the Church, but in the source from which they came, then the New Testament was in principle complete when the various elements coming from the source had been written. That is to say, when once the principle of the canon has been determined, then ideally its extent is fixed and the canon is complete when the books which by principle belong to it have been written. (Metzger 283-84)[84]

Metzger, The Canon of the New Testament

Truly, if the New Testament documents are going to be canonical, then they must have been such due to their inherent value which was theirs as they were completed by God’s spokesperson.

In the end, it is argued in agreement with E. Schnabel, that while Marcion may be the first known person to have put together a list of books in the canonical sense, which provoked the church “to draw up its own list,” he did not, however, create the fundamental idea of that a book (or list of books) could be authoritative (i..e, canonical)–an idea which had existed in earlier Christian times.[85]

Endnotes

- Eckhard Schnabel, “History, Theology, and the Biblical Canon: An Introduction to Basic Issues,” Them 20.2 (1995): 19–21.

- Wilber T. Dayton, “Factors Promoting the Formation of the New Testament Canon,” JETS 10 (1967): 28–35.

- Nicolaas Appel, “The New Testament Canon: Historical Process and Spirit’s Witness,” TS 32.1 (1971): 629.

- Everett Ferguson, “Factors Leading to the Selection and Closure of the New Testament Canon: A Survey of Some Recent Studies,” in The Canon Debate, edited by Lee M. McDonald and James E. Sanders (Peabody: Hendrickson, 2002), 295.

- Ferguson, “Factors,” 309.

- F. F. Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are they Reliable? 5th ed. (repr., Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), 22.

- F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1988), 134.

- Milton Fisher, “The Canon of the New Testament,” The Origin of the Bible, ed. Philip Comfort (Wheaton: Tyndale, 2003), 65.

- Fisher, “Canon of the New Testament,” 69.

- Simon J. Kistemaker, “The Canon of the New Testament,” JETS 20 (1977): 10.

- Schnabel, “History,” 19.

- Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church (1858–1867; repr., Peabody: Hendrickson, 2002), 2:484.

- Schaff, History, 2:484.

- Ibid.

- Bruce M. Metzger, The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1997), 90.

- Edwin Yamauchi, “The Gnostics and History,” JETS 14 (1971): 29.

- Harold O. J. Brown, Heresies: Heresy and Orthodoxy in the History of the Church (Peabody: Hendrickson, 2000), 39.

- Brown, Heresies, 39.

- Brown, Heresies, 40.

- Yamauchi, “Gnostics and History,” 29.

- All Ante-Nicene Fathers quotations are taken from Ante-Nicene Fathers, edited by Alexander Robertson and James Donaldson (1885; repr., Peabody: Hendrickson, 2004).

- Ferguson, “Factors,” 309-10.

- This is much like how the views of Porphyry, the neo-platonic antagonist of Christianity, are known (Bruce, Canon, 141).

- Metzger, Canon, 91; Ferguson, “Factors,” 309.

- John Barton, “Marcion Revisited,” The Canon Debate, edited by Lee M. McDonald and James E. Sanders (Peabody: Hendrickson, 2002), 341–54. 353; Metzger, Canon, 91.

- Schaff, History, 2.484.

- Barton, “Marcion Revisited,” 341.

- Schaff, History, 2.484.

- Schaff, History, 2.484-85; Yamauchi, “Gnostics and History,” 30-33.

- Barton, “Marcion Revisited,” 341.

- Justin Martyr, First Apology 26. Translated by Marcus Dods and George Reith in Ante-Nicene Fathers, edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature, 1885). Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight.

- Barton, “Marcion Revisited,” 341.

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1:27:2. Translated by Alexander Roberts and William Rambaut in Ante-Nicene Fathers, edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature, 1885). Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight.

- Tertullian, Prescription Against Heresies 38; David W. Bercot, ed., “Marcion,” A Dictionary of Early Christian Beliefs (1998, reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2000), 420.

- Barton, “Marcion Revisited,” 344.

- Barton, “Marcion Revisited,” 345.

- Ibid., 345.

- Bruce, Canon, 134.

- Ibid., 134.

- Bruce, Canon 136

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1:27:2; Tertullian, Prescription Against Heresies 38.

- Thomas D. Lea, and David Alan Black, The New Testament: Its Background and Message, 2nd ed. (Nashville: Broadman, 2003), 73; Merrill C. Tenney and Walter M. Dunnett, New Testament Survey. Rev. ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001), 408; Metzger, Canon, 98.

- Harry Y. Gamble, The New Testament Canon: Its Making and Meaning (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1985), 15–18; BDAG 507–08.

- Gamble, Canon, 15; MM 320.

- Gamble, Canon, 15

- Gamble, Canon, 15

- Richard N. Soulen and R. Kendall Soulen. Handbook of Biblical Criticism, 3rd ed. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001), 29.

- Cecil M. Robeck, Jr., “Canon, Regulae Fidei, and Continuing Revelation in the Early Church,” Church, Word, and Spirit: Historical and Theological Essays in Honor of Geoffrey W. Bromiley, edited by James E. Bradley and Richard A. Muller (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987), 70; Gamble, Canon, 16–17; Linda L. Belleville, “Canon of the New Testament,” Foundations for Biblical Interpretation, edited by. David S. Dockery, Kenneth A. Matthews, and Robert B. Sloan. Nashville: Broadman, 1994. 375: Lea and Black, The New Testament, 70–71.

- Kistemaker, “Canon,” 13.

- D. A. Carson, Douglas J. Moo, and Leon Morris, An Introduction to the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1992), 367–71, 433–35.

- The main list of this section comes from Dowell Flatt, “Why Twenty-Seven New Testament Books?” Settled in Heaven: Applying the Bible to Life, edited by David Lipe (Henderson, TN: Freed-Hardeman University, 1996), 139; cf. James A. Brooks, Broadman Bible Commentary, edited by Clifton J. Allen (Nashville: Broadman, 1969), 8:18–21.

- Paul L. Maier, translator, Eusebius: The Church History – A New Translation with Commentary (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1999), 127.

- On illiteracy see Alan Millard, Reading and Writing in the Time of Jesus (Sheffield, England: Sheffield, 2001), 154–84. On the point that there is no explicit command by Jesus to write biblical books see D. I. Lanslots, The Primitive Church, Or The Church in the Days of the Apostles (1926, reprint, Rockford, IL: Tan Books, 1980), 102–09.

- Kurt Aland, “The Problem of Anonymity and Pseudonymity in Christian Literature of the First Two Centuries,” JETS 12 (1961), 47.

- King McCarver, “Why Are These Books in the Bible? – New Testament,” God’s Word for Today’s World: The Biblical Doctrine of Scripture, edited by Don Jackson, et al. (Kosciusko, MI: Magnolia Bible College, 1986), 88; Kistemaker, “Canon,” 13.

- Michael W. Holmes, editor, The Apostolic Fathers: Greek Texts and English Translations, rev. ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2004), 23, 104; Robert E. Picirilli, “Allusions to 2 Peter in the Apostolic Fathers,” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 33 (1988), 57–83.

- Richard J. Bauckham, Jude, 2 Peter (Waco, TX: Word, 1983), 157–58.

- Werner Georg Kümmel, Introduction to the New Testament, translated by Howard Clark Kee (Nashville: Abingdon, 1986), 387.

- D. Edmond Hiebert, “Selected Studies from 2 Peter Part 4: Directives for Living in Dangerous Days: An Exposition of 2 Peter 3:14-18a,” BSac 141 (1984): 336.

- Jerome H. Neyrey, 2 Peter, Jude: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (New York: Doubleday, 1993), 250.

- Bauckham, Jude, 2 Peter, 328.

- BDAG 948.

- Bauckham, Jude, 2 Peter, 329.

- Hiebert, “Selected Studies,” 336; Thomas R. Schreiner, 1, 2 Peter, Jude (Nashville: Broadman, 2003), 397–98; L&N 1:61.

- BDAG 602; W. Günther H. Krienke, “Remnant, Leave,” NIDNTT 3:252.

- Raymond C. Kelcy, The Letters of Peter and Jude (Abilene, TX: Abilene Christian University Press, 1987), 162; Tord Fornberg, An Early Church in a Pluralistic Society: A Study of 2 Peter, translated by Jean Gray (Sweden: Boktryckeri, 1977), 22; Krienke, “Remnant, Leave,” 252.

- Bauckham, Jude, 2 Peter, 333.

- Earl J. Richard, Reading 1 Peter, Jude, and 2 Peter: A Literary and Theological Commentary (Macon, GA: Smyth, 2000), 390.

- Luke T. Johnson, The Writings of the New Testament: An Interpretation (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1986), 443–44; Richard, 1 Peter, Jude, and 2 Peter, 388; Neyrey, 2 Peter, Jude, 250.

- McCarver, “Why Are These Books in the Bible?,” 88; E. Randolph Richards, “The Codex and the Early Collection of Paul’s Letters,” BBR 8 (1998): 155–66.

- McCarver, “Why Are These Books in the Bible?” 88.

- Richards, “The Codex,” 158–59.

- Richards, “The Codex,” 162–66.

- Richards, “The Codex,” 161.

- Richards, “The Codex,” 159–62.

- Richards, “The Codex,” 165.

- Richards, “The Codex,” 165–66.

- Kistemaker, “Canon,” 13.

- Kistemaker, “Canon” 13; McCarver 88-90; Flatt 140-42

- C. F. D. Moule, The Birth of the New Testament (London: Black, 1973), 198.

- Bruce 134

- Edward W. Bauman, An Introduction to the New Testament (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1961), 175.

- Ferguson, “Factors,” 309–10.

- Metzger, Canon, 283–84

- Schnabel, “History, Theology,” 19.

Bibliography

Aland, Kurt. “The Problem of Anonymity and Pseudonymity in Christian Literature of the First Two Centuries.” Journal of Theological Studies 12 (1961): 39-49.

Appel, Nicolaas. “The New Testament Canon: Historical Process and Spirit’s Witness.” Theological Studies 32.1 (1971): 627-46.

Barton, John. “Marcion Revisited.” The Canon Debate. Eds. Lee M. McDonald and James E. Sanders. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2002. 341-54.

Bauckham, Richard J. Jude, 2 Peter. Word Biblical Commentary. Vol. 50. Gen. eds. David A. Hubbard and Glenn W. Barker. Waco, TX: Word, 1983.

Bauman, Edward W. An Introduction to the New Testament. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1961.

(BDAG) Bauer, Walter, F.W. Danker, William F. Arndt, and F. Wilbur Gingrich. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other Early Christian Literature. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Belleville, Linda L. “Canon of the New Testament.” Foundations for Biblical Interpretation: A Complete Library of Tools and Resources. Eds. David S. Dockery, Kenneth A. Matthews, and Robert B. Sloan. Nashville: Broadman, 1994.

Bercot, David W. Editor. A Dictionary of Early Christian Beliefs. 1998. Reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2000.

Brooks, James A. Broadman Bible Commentary. Vol. 8. Ed. Clifton J. Allen. Nashville: Broadman, 1969.

Brown, Harold O. J. Heresies: Heresy and Orthodoxy in the History of the Church. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2000.

Bruce, F.F. The Canon of Scripture. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1988.

—. The New Testament Documents: Are they Reliable? 5th ed. Leicester/Grand Rapids: InterVarsity/Eerdmans, 2000.

Carson, D.A., Douglas J. Moo, and Leon Morris. An Introduction to the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1992.

Dayton, Wilber T. “Factors Promoting the Formation of the New Testament Canon.” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 10 (1967): 28-35.

Ferguson, Everett. “Factors Leading to the Selection and Closure of the New Testament Canon: A Survey of Some Recent Studies.” The Canon Debate. Eds. Lee M. McDonald and James E. Sanders. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2002. 295-320.

Fisher, Milton. “The Canon of the New Testament.” The Origin of the Bible. Ed. Philip Comfort. Wheaton: Tyndale, 2003. 65-78.

Flatt, Dowell. “Why Twenty Seven New Testament Books?” Settled in Heaven: Applying the Bible to Life. Ed. David Lipe. Annual Freed-Hardeman University Lectureship. Henderson, TN: Freed-Hardeman UP, 1996. 138-45.

Fornberg, Tord. An Early Church in a Pluralistic Society: A Study of 2 Peter. Trans. Jean Gray. Sweden: Boktryckeri, 1977.

Gamble, Harry Y. The New Testament Canon: Its Making and Meaning. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1985.

Hiebert, D. Edmond. “Selected Studies from 2 Peter Part 4: Directives for Living in Dangerous Days: An Exposition of 2 Peter 3:14-18a.” Bibliotheca Sacra 141 (1984): 330-40.

Holmes, Michael W. Ed. The Apostolic Fathers: Greek Texts and English Translations. Rev. ed. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2004.

Johnson, Luke T. The Writings of the New Testament: An Interpretation. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1986.

Kelcy, Raymond C. The Letters of Peter and Jude. The Living Word Commentary: New Testament. Vol. 17. Ed. Everett Ferguson. Abilene, TX: Abilene Christian UP, 1987.

Kistemaker, Simon J. “The Canon of the New Testament.” Journal of Evangelical Theological Society 20 (1977): 3-14.

Krienke, W. Günther H. “Remnant, Leave.” New International Dictionary of the New Testament Theology. Vol. 3. Ed. Colin Brown. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1978. 247-54.

Kümmel, Werner Georg. Introduction to the New Testament. Trans. Howard Clark Kee. Nashville: Abingdon, 1986.

Lanslots, D. I. The Primitive Church, Or The Church in the Days of the Apostles. 1926. Reprint, Rockford, IL: Tan Books, 1980.

Lea, Thomas D., and David Alan Black. The New Testament: Its Background and Message. 2nd ed. Nashville: Broadman, 2003.

(L&N) Louw, Johannes P., and Eugene A. Nida. Eds. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament Based on Semantic Domains. 2nd ed. New York: United Bible Society, 1989. 2 vols.

Maier, Paul L. Trans. Eusebius: The Church History – A New Translation with Commentary. Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1999.

McCarver, King. “Why Are These Books in the Bible? – New Testament.” God’s Word for Today’s World: The Biblical Doctrine of Scripture. Don Jackson, Samuel Jones, Cecil May, Jr., and Donald R. Taylor. Kosciusko, MI: Magnolia Bible College, 1986.

Metzger, Bruce M. The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1997.

Millard, Alan. Reading and Writing in the Time of Jesus. Sheffield, England: Sheffield, 2001.

Moule, C.F.D. The Birth of the New Testament. London: Black, 1973.

(MM) Moulton, James H., and George Milligan. The Vocabulary of the Greek Testament. 1930. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1997.

Neyrey, Jerome H. 2 Peter, Jude: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Anchor Bible. Vol. 37 C. Gen. ed. William F. Albright and David Noel Freedman. New York: Doubleday, 1993

Picirilli, Robert E. “Allusions to 2 Peter in the Apostolic Fathers.” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 33 (1988): 57-83.

Richard, Earl J. Reading 1 Peter, Jude, and 2 Peter: A Literary and Theological Commentary. Reading the New Testament Series. Macon, GA: Smyth, 2000.

Richards, E. Randolph. “The Codex and the Early Collection of Paul’s Letters.” Bulletin for Bulletin Research 8 (1998): 151-66.

Robeck, Cecil M., Jr. “Canon, Regulae Fidei, and Continuing Revelation in the Early Church.” Church, Word, and Spirit: Historical and Theological Essays in Honor of Geoffrey W. Bromiley. Eds. James E. Bradley and Richard A. Muller. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987.

Robertson, Alexander, and James Donaldson. Eds. Ante-Nicene Fathers. Vols.1, 3-4. 1885. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2004.

Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church. Vols. 1-3. 1858-1867. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2002.

Schnabel, Eckhard. “History, Theology, and the Biblical Canon: An Introduction to Basic Issues.” Themelios 20.2 (1995): 16-24.

Schreiner, Thomas R. 1, 2 Peter, Jude. The New American Commentary. Vol. 37. Gen. ed. E. Ray Clendenen. Nashville: Broadman, 2003.

Soulen, Richard N., and R. Kendall Soulen. Handbook of Biblical Criticism. 3rd ed. Rev. and expanded. Louisville: WJK, 2001.

Tenney, Merrill C., and Walter M. Dunnett. New Testament Survey. Rev. ed. Revised by Walter M. Dunnett. Grand Rapids/Leicester: Eerdmans/InterVarsity, 2001.

Yamauchi, Edwin. “The Gnostics and History.” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 14.1 (1971): 29-40.