A person of faith often assumes that there are no problems ascertaining the wording of certain passages. But reality demonstrates that there are instances where this proves to be untrue. What a believer expects God to do in His providential care of the planet may not always line up with how life unfolds itself, but such disorientation has been common among the faithful.

Despite all the miracles employed to compel Pharoah to release the Israelites from Egypt, when the environment became less than comfortable fear and panic overcame God’s people (Exod 14). Even Moses had initial problems with understanding the situation he was faced with when he was sent to Pharoah to have him release the Israelites (Exod 5). Examples could be multiplied to demonstrate that a person of faith at times needs “more” in order to calm their nerves.

The following brief study gives attention to the textual basis of the Old Testament, considering a few lines of thought that contribute to a more informed outlook on how copies of the Hebrew Bible have been transmitted into modern hands, and what the sources of the copies used today so that translators are able to produce translations of the Hebrew Bible.

It must be emphasized that this is not an exhaustive treatment of the subject. So much more is available for analysis; be that as it may, a survey of this material is sufficient to adequately support the above affirmation of the adequate veracity of the Hebrew Bible.

A Skeptic’s Concern

A skeptical approach to the Bible essentially argues that for a collection of books so old, for a collection of books that have passed through so many hands, or for a collection of anonymously published volumes, it is a hard sell to affirm that the Bible – here the Hebrew Bible – is trustworthy in any sense.

Regarding the textual certainty of the Bible in general, skeptic Donald Morgan puts the matter bluntly in the following words:

No original manuscripts exist. There is probably not one book that survives in anything like its original form. There are hundreds of differences between the oldest manuscripts of any one book. These differences indicate that numerous additions and alterations were made to the originals by various copyists and editors.[1]

The argument basically affirms that there is no way for the Bible to be an accurate record of the words of God, and therefore, it is not “trustworthy.” The sheer force of this argument is designed to rob the Bible believer’s faith in God. Implicit with this is the futility of having a religion founded upon the Bible’s guidance.

What can be said of this dire depiction, except that one must not be persuaded by mere affirmations, but instead by the available evidence. Not only is it paramount to see the evidence, but it is imperative that a proper evaluation is given to it.

The OT Accurately Transmitted

The Scribal Evidence

The overall scribal evidence suggests that the Hebrew Bible has been adequately preserved. The “scribe” trade goes back very early in recorded antiquity and therefore is a field of has a rich heritage of scholarship and workmanship behind it.[2] J. W. Martin notes that the field of transmitting literature is a known trade skill from the 2nd millennium B.C. and observes, “men were being trained not merely as scribes, but as expert copyists.”[3] Copying occurred during the Babylonian exile. F. C. Grant writes, “in far-away Babylonia the study and codification, the copying and interpretation of the Sacred Law had steadily continued.”[4]

This means that extending back beyond the time of Abraham (19th century B.C.) and Moses (15th century B.C.), down to the time of the exilic and post-exilic scribes (the predecessors to the “scribes who copied and explained the Law in the New Testament times”),[5] “advanced” and “scrupulous” methods would likely be used to copy any text, including the Hebrew canon.

The next question in need of an answer, though, is: what were those methods? Briefly, observe the mentality and professionalism which exemplify the sheer reverential ethic towards the transmission of the Biblical text characterized by the scribes.

The Hebrew Scribes revered the sanctity of the Scriptures. Moses commanded the people not to “add to the word,” nor to “take from it” (Deut 4:2). The Hebrews respected this command. Josephus weighs in as support for this point. In arguing for the superiority of the Hebrew Bible against the conflicting mythologies of the Greeks fraught with evident contradicting alterations to their content, Josephus bases his argument upon the reverential mentality towards these writings.

Josephus testifies to this sense of reverence (Against Apion 1.8.41-42):

[41] It is true, our history hath been written since Artaxerxes very particularly, but hath not been esteemed of the like authority with the former by our forefathers, because there hath not been an exact succession of prophets since that time; [42] and how firmly we have given credit to those books of our own nation, is evident by what we do; for during so many ages as have already passed, no one has been so bold as either to add anything to them, to take anything from them, or to make any change in them; but it becomes natural to all Jews, immediately and from their very birth, to esteem those books to contain divine doctrines, and to persist in them, and, if occasion be, willingly to die for them.[6]

William Whiston, Translator

Even though there are variants, produced by scribes, the fundamental historical truth stresses that the Hebrew scribes revered the Scriptures and dared never to add or take away from them. This important truth must not be forgotten. Moreover, this fact emphasizes the great care they had with the transmission of the text.

The scribal methods changed as time progressed, and this seems to be for the better and for the worst. One thing is transparent, however, and that is this: consistent with the reverential appreciation of the scriptures, the Hebrew scribes exercised acute professionalism in their methods, however superstitious they were at times. Rabbinic literature testifies to the early scribal school. Clyde Woods reproduces 17 crucial rabbinic rules demonstrating the rigors of the early scribal methodology.[7] The specifics concerning the writing materials, the preparation of the document, the veracity of the authenticity of the template, the conduct displayed when writing divine names, and other critical rules are thus enumerated underscoring the diligent professionalism of the early scribes.

The Masoretes succeeded and exceeded these scribes as a professional group of transmitters of the Hebrew Bible, laboring from A.D. 500 to A.D. 1000.[8] Lightfoot summarizes a number of procedures the Masoretes employed to “eliminate scribal slips of addition and omission.”[9] The Masoretes counted and located the number of “verses, words, and letters of each book,” thereby passing on the text that they have received. This intricate methodology in preservation is of extreme importance in modern textual studies,[10] and answers the reason why these reliable “medieval manuscripts” are commonly the underlying text of modern English translations[11] and represented in the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (cf. English Standard Version).[12]

The concern for the accurate preservation of the Biblical text cannot, however, dismiss the fallible humanity which copied the text by hand, thereby producing inevitable scribal variations.[13] René Paché recounts the “herculean” endeavors of scholars evaluating the variants which have “crept into the manuscripts of the Scriptures” (e.g. B. Kennicott, Rossi, and J. H. Michaelis). These labors have also encompassed the analysis of the oldest versions and numerous citations and allusions from Jewish and Christian works. Robert D. Wilson’s observations in his work, A Scientific Investigation of the Old Testament, noted that the 581 Hebrew manuscripts studied by Kennicott are composed of 280 million letters comprised of only 900,000 variants. These variants are boiled down to 150,000 because 750,000 are “insignificant changes” of letter switches.[14]

This is represented as 1 variant for every 316 letters, but putting these unimportant variants aside, the count stands at 1 variant for every 1,580 letters. Moreover, “very few variants occur in more than one of the 200-400 manuscripts of each book of the Old Testament.”[15] The point that needs recognition, however, is that we must recognize that the scribes have done their best, but there are variations that must be accounted for. These variations are not sufficient enough to call into question the adequate preservation of the Hebrew Bible.

Textual Evidence

After evaluating some of the problems in the textual evidence for the Old Testament, it can be said that the overall material adequately preserves the Hebrew Bible. This investigation is comparable to a roller coaster. There are both ups and downs, making one more confident while at the same time bringing some concern. For example, Peter Craigie notes, “there is no original copy of any Old Testament book; indeed, not even a single verse has survived in its original autograph. This is not a radical statement, simply a statement of fact.”[16]

The Bible believer might feel a bit disconcerted to know this fact, but there is no genuine need to feel this way. Truth endures because of its very nature no matter if one destroys the materials upon which it is written (Jer 36:23-32). Moreover, the scribal evidence adequately demonstrates an amazingly high level of accurate transmission and preservation of the Old Testament, even though the autographs are not available. One might speculate as to why these important documents are not providentially preserved for posterity, but the observation that such a course of action “is a highly dangerous procedure” is promptly recognized.[17]

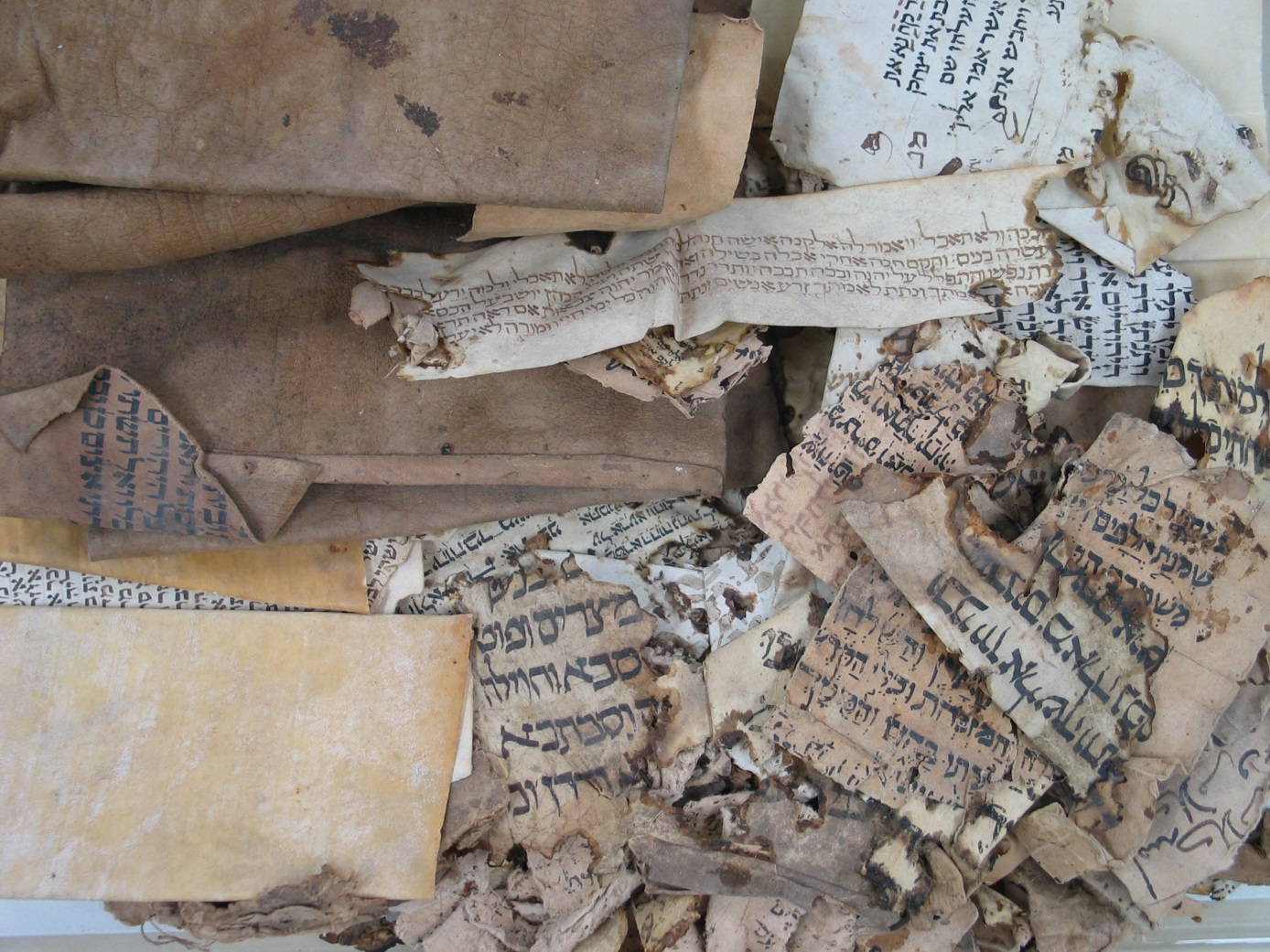

Nevertheless, there are historical issues relating to this question and to the question of why there are such a small number of manuscript copies of the Old Testament when compared to the textual evidence of the New Testament. The most important fact is that the Hebrew scribes destroyed old manuscripts (autographs and copies). Clyde M. Woods writes:

The relative paucity [i.e. smallness of number] of earlier Hebrew manuscripts is due not only to the perishable nature of ancient writing materials (skins and papyri) and to the effort of hostile enemies to destroy the Hebrew Scriptures, but, perhaps more significantly, to the fact that the Jews evidently destroyed some worn out manuscripts to prevent their falling into profane hands.[18]

This explains why there is comparatively less textual witness for the Old Testament than for the New, however, as Donald Demaray notes, “there is the compensating factor that the Jews copied their Scriptures with greater care than did the Christians.”[19] There are accounts of scribes having burial ceremonies for the manuscripts,[20] and the storage “of scrolls [in a “Genizah” depository] no longer considered fit for use.”[21]

A second major factor is the A.D. 303 declaration by Emperor Diocletian to destroy any “sacred” literature associated with the Christian religion.[22] F. C. Grant frames the significance as follows:

As never before, the motive of the Great Persecution which began in 303 was the total extirpation of Christianity: […]. The first of Diocletian’s edicts directed to this end prohibited all assemblies of Christians for purposes of worship, and commanded that their churches and sacred books should be destroyed.[23]

This would further contribute to the lack of Hebrew Bible manuscripts.

Modern manuscript evidence for the Hebrew Bible, therefore, does not include the autographa (“original manuscripts”) and is generally never expected to, as desirable as the obtainment of these documents is.[24] What remains is the collection of manuscripts which together allow textual scholars to reproduce as close as possible the Hebrew Old Testament. This body of textual evidence goes very far to close the gap between the present day and the autographa. What are these manuscript witnesses to the Hebrew Bible? There are primary and secondary witnesses but where space is limited to the manuscripts.

Bruce Waltke observes that the textual witnesses to the text are the extant Hebrew manuscripts and Hebrew Vorlage obtained from the early versions of the Hebrew text.[25] While the term “manuscript” is typically recognized, the term Vorlage is probably unfamiliar to the general Bible student. This term refers to the text that “lies before” the translation or a theoretical “prototype or source document” from which it is based.[26] The Masoretic text (MT), the Samaritan Pentateuch (SP), and the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) are the principal manuscript witnesses. These manuscripts coupled with the Vorlage are the “documents” at our disposal.

Craigie’s presentation on this material[27] when compared to Waltke leaves something to be desired, and that something is more data and deeper investigation. However, Craigie presents the evidence that the manuscript evidence (including early translations) extends from the 2nd century B.C to the MT of the late 9th century B.C.[28] Leaving a considerable gap, as he notes, of “several centuries, the time varying from one Old Testament book to another, between the earliest extant manuscripts and no longer existing original manuscripts.”[29]

Waltke presents a fuller presentation of the two substantiating Craigie’s observations and would extend from the available data that the Vorlage of some of the DSS and SP points to a Proto-MT at least somewhere in the 5th century B.C.[30] Moreover, the oldest evidence is found in 2 extremely small silver rolls containing the Aaronic priestly blessing from Numbers 6:24-26, dating to the 7th or 6th centuries B.C.[31] The text reads:

May Yahweh bless you and keep you;

May Yahweh cause his face to

Shine upon you and grant you

Peace

(Michael D. Coogan)

Consequently, the worst case holds that the textual evidence goes only to the 2nd century, while the best case goes back some 300-500 years further back to a purer source as of yet unavailable.

H. G. G. Herklots has compiled a generous amount of information concerning the production of harmonization work which underlies the works of present-day manuscripts.[32] By doing this Herklots highlights that there are variations in the textual witnesses that the early stewards of the text attempted to dispose of but this has in some sense complicated the matter, making the study more laborious than it already is.[33] Variations are not as problematic as the skeptic supposes. To be sure, there are occasions of serious textual dissonance, but these are far from the plethoras of insignificant, obvious, and correctable variations.[34]

Waltke affirms, that “90 percent of the text contains no variants,” and of the remnant “10 percent of textual variations, only a few percent are significant and warrant scrutiny; 95 percent of the OT is therefore textually sound.”[35] Douglas Stuart notes that when considering the variations, “it is fair to say that the verses, chapters, and books of the Bible would read largely the same, and would leave the same impression with the reader, even if one adopted virtually every possible alternative reading.”[36] The variations of the extant textual evidence hardly, therefore, pose an indomitable problem to the adequate preservation of the Old Testament. The skeptic’s argument has no leg to stand upon.

Extra-Hebrew Bible Sources

Besides the extant Biblical literature of the Hebrew Bible, there are miscellaneous sources that demonstrate the veracity of the text, and implicitly note the accountability of the Hebrew Bible to a textual investigation. While these witnesses cannot reproduce the entire Old Testament, they can be compared with the manuscript evidence for accuracy and enlightened evidence when certain passages or words appear obscure. Briefly, consider two sources.

First, the Targums are a set of Jewish works in Aramaic that are paraphrastic (i.e. “interpretive translation”) of parts of the Old Testament.[37] Targums are said to be used in the synagogue to give the Aramaic-speaking Jews the “sense” of the Hebrew Bible.[38] This is comparable to the verbal translation that had to occur at the inauguration of the Law under Ezra, where there were assistants who “gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading” (Neh 8:8 ESV).

Targums have been written upon every section of the Hebrew Bible; they ranged from “very conservative” to “interpretive” (Onkelos and Jonathon respectively), and are useful for the light they show upon traditional Jewish interpretation.[39] In the history of the transmission of the Hebrew Bible, at times the Targum was placed along the side of a Hebrew text, a Greek text, and a Latin text (as in the Complutensian Polyglot) to “enable a reader with little Hebrew to understand the meaning of the Scriptures in his own language.”[40] It seems agreeable to suggest and affirm that the Targum serves as an appropriate and practical source to obtain a general understanding of the Hebrew text, which will definitely aid the textual scholar in analyzing obscure passages.

Second, there is the New Testament, which is a virtual galaxy of Old Testament citations and allusions as it connects Jesus and his followers as a continuation -fulfillment- of its message. Consequently, it serves as a proper witness to the passages cited or alluded to. E. E. Ellis writes:

there are some 250 express citations of the Old Testament in the New. If indirect or partial quotations and allusions are added, the total exceeds a thousand.[41]

The Greek New Testament, published by the United Bible Society, has 2 notable reference indexes. The first index lists the “Quotations” while the other catalogs “Allusions and Verbal Parallels.”[42]

The New Testament writers used and quoted not only the Hebrew Bible, but also the LXX (with some variations suggesting different Greek translations), and other sources such as the Old Testament Targums.[43] In addition, the New Testament, in terms of textual evidence (manuscript, early version, and patristic quotations), is the most attested document from antiquity[44] emphasizes the reliability of the New Testament evidence for the Old Testament.[45]

Concluding Thoughts

In summation, we have examined some of the evidence in a survey and observed that the typical skeptical claim against the Bible is fallacious. We are more than confident that the textual transmission of the Bible has adequately preserved the Bible. There are so many avenues from which data pours in that for all practical purposes the gap from these extant materials to the originals is irrelevant. Gaps of greater magnitude exist for other works of antiquity, but no finger of resistance is pressed against their adequate representation of the autographic materials.

The Bible experiences this sort of attack partly because ignorant friends of the Bible fighting with a broken sword affirm that we have the Bible and that it has no textual problems. Other times, skeptics misrepresent textual studies of the Bible in order to support their case that the Bible is not the inerrant inspired word of God. Be that as it may, the scribal evidence demands that the scribes held a high reverence and professionalism in the transmission of the text, the textual evidence is, though having some problems, near 100 percent sound. Moreover, the New Testament and Talmud are examples of sources that uphold the Biblical text and allow textual scholars to examine the accuracy of the textual data.

Finally, the skeptical attack has been viewed a considered only for it to be concluded that it is fallacious and of no need to be considered a viable position based on the evidence. In connection with this conclusion, observe some observations by Robert D. Wilson and Harry Rimmer. Rimmer writes that a scientific approach to the Bible inquiry is to adopt a hypothesis and then test it and see if there are supportive data that establishes it. He writes:

If the hypothesis cannot be established and if the facts will not fit in with its framework, we reject that hypothesis and proceed along the line of another theory. If facts sustain the hypothesis, it then ceases to be theory and becomes an established truth.[46]

Wilson makes a similar argument and ties an ethical demand to it. After ably refuting a critical argument against Daniel, Wilson remarks that when prominent critical scholars make egregious affirmations adequately shown to be so, “what dependence will you place on him when he steps beyond the bounds of knowledge into the dim regions of conjecture and fancy?.”[47]

Endnotes

- Donald Morgan, “Introduction to the Bible and Biblical Problems,” Infidels Online (Accessed 2003). Mr. Morgan is just a classic example of the skepticism that many share regarding the integrity of the biblical record.

- Daniel Arnaud, “Scribes and Literature,” NEA 63.4 (2000): 199.

- J. W. Martin, et al., “Texts and Versions,” in The New Bible Dictionary, eds. J. D. Douglas (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1962), 1254.

- Fredrick C. Grant, Translating the Bible (Greenwich, CT: Seabury, 1961), 8 (emph. added).

- Grant, Translating the Bible, 10-11.

- Flavius Josephus, The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, trans. William Whiston (repr., Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1987).

- Clyde M. Woods, “Can we be Certain of the Text? – Old Testament,” in God’s Word for Today’s World: The Biblical Doctrine of Scripture (Kosciusko, MI: Magnolia Bible College, 1986), 98.

- Martin, et al., “Texts and Versions,” 1255; René Paché, The Inspiration and Authority of Scripture, trans. Helen I. Needham (Chicago, IL: Moody, 1969), 187.

- Neil R. Lightfoot, How We Got the Bible, 2d ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2001), 92.

- Lightfoot, How We Got the Bible, 92.

- Peter C. Craigie, The Old Testament: Its Background, Growth, and Content (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1986), 32.

- English Standard Version of The Holy Bible (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2001), ix.

- Lightfoot, How We Got the Bible, 91.

- Robert D. Wilson, A Scientific Investigation of the Old Testament, revised ed., Edward J. Young (Chicago, IL: Moody, 1967), .

- ctd. in Paché, Inspiration and Authority of Scripture, 189–90.

- Craigie, The Old Testament, 34.

- Dowell Flatt, “Can we be Certain of the Text? – New Testament,” in God’s Word for Today’s World: The Biblical Doctrine of Scripture (Kosciusko, MI: Magnolia Bible College, 1986), 104: “The books of the New Testament were originally copied by amateurs,” the variants multiplied from persecution pressures and translations issues up until the “standardization of the text” in the 4th to 8th centuries A.D.

- Woods, “Can we be Certain of the Text?,” 96.

- Donald E. Demaray, Bible Study Sourcebook, (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1964), 35; Flatt, “Can we be Certain of the Text?,” 106.

- Lightfoot, How We Got the Bible, 90.

- Martin, et al., “Texts and Versions,” 1256-57; Paché, Inspiration and Authority of Scripture, 187-88; F. C. Grant notes that the Synagogue of Old Cairo’s Geniza has been found, throwing “great light upon Biblical studies” (Translating the Bible, 40). Biblical scrolls were discovered from 1890 and, onwards including Targums and rabbinic literature (Martin, et al., “Texts and Versions,” 1256-57).

- Michael Grant, The Roman Emperors: a Biographical Guide to the Rulers of Imperial Rome 31 B.C.–A.D. 476 (1985; repr., New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, 1997), 208.

- Grant, Translating the Bible, 208.

- Lightfoot, How We Got the Bible, 90.

- Bruce K. Waltke, “Old Testament Textual Criticism,” in Foundations for Biblical Interpretation, eds. David S. Dockery, et al. (Nashville, TN: Broadman, 1994), 159-68.

- Matthew S. DeMoss, Pocket Dictionary for the Study of New Testament Greek (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity, 2001), 128.

- Craigie, The Old Testament, 32-37.

- Craigie, The Old Testament, 36, 32.

- Craigie, The Old Testament, 34.

- Waltke, “Old Testament Textual Criticism,” 162.

- Waltke, “Old Testament Textual Criticism,” 163.

- H. G. G. Herklots, How Our Bible Came to Us: Its Texts and Versions (New York, NY: Oxford University, 1957), 29-40, 109-23

- Herklots, How Our Bible Came to Us, 116-23, Waltke, “Old Testament Textual Criticism,” 164-167.

- Waltke, “Old Testament Textual Criticism,” 157.

- Waltke, “Old Testament Textual Criticism,” 157-58.

- qtd. in Waltke, “Old Testament Textual Criticism,” 157.

- D. F. Payne, “Targums,” in The New Bible Dictionary, ed. J. D. Douglas (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1962), 1238.

- Payne, “Targums,” 1238.

- Payne, “Targums,” 1239.

- Herklots, How Our Bible Came to Us, 35-36.

- E. E. Ellis, “Quotations (in the New Testament),” in The New Bible Dictionary, ed. J. D. Douglas (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1962), 1071.

- Barbara Aland, et al., eds., The Greek New Testament, 4th rev. ed. (Stuttgart: United Bible Societies, 2002), 887-901.

- Ellis, “Quotations (in the New Testament),” 1071.

- Wayne Jackson, Fortify Your Faith In an Age of Doubt (Montgomery, AL: Apologetics Press, 1974), 70-75.

- Harry Rimmer, Internal Evidence of Inspiration, 7th edition (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1946), 36.

- Wilson, A Scientific Investigation of the Old Testament, 98.

Bibliography

Aland, Barbara, et al. Editors. The Greek New Testament. 4th rev. ed. Stuttgart: United Bible Societies, 2002.

Arnaud, Daniel. “Scribes and Literature.” NEA 63.4 (2000): 199.

Craigie, Peter C. The Old Testament: Its Background, Growth, and Content. Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1986.

Demaray, Donald E. Bible Study Sourcebook. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1964.

DeMoss, Matthew S. Pocket Dictionary for the Study of New Testament Greek. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2001.

Ellis, E. E. “Quotations (in the New Testament).” Page 1071 in The New Bible Dictionary. Edited by J. D. Douglas. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1962.

Flatt, Dowell. “Can we be Certain of the Text? – New Testament.” Pages 103-10 in God’s Word for Today’s World: the Biblical Doctrine of Scripture. Don Jackson, Samuel Jones, Cecil May, Jr., and Donald R. Taylor. Kosciusko, MS: Magnolia Bible College, 1986.

Grant, Fredrick C. Translating the Bible. Greenwich, CT: Seabury, 1961.

Grant, Michael. The Roman Emperors: a Biographical Guide to the Rulers of Imperial Rome 31 B.C.–A.D. 476. 1985. Repr., New York, NY: Barnes, 1997.

Herklots, H. G. G. How Our Bible Came to Us: Its Texts and Versions. New York, NY: Oxford University, 1957.

Jackson, Wayne. Fortify Your Faith In an Age of Doubt. Montgomery, AL: Apologetics Press, 1974.

Josephus, Flavius. The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged. Translated by William Whiston. Repr. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1987.

Lightfoot, Neil R. How We Got the Bible. 2d edition. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2001.

Martin, W. J., et. al. “Texts and Versions.” Pages 1254-69 in The New Bible Dictionary. Edited by J. D. Douglas. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1962.

Morgan, Donald. “Introduction to the Bible and Biblical Problems.” Infidels Online.

Paché, René. The Inspiration and Authority of Scripture. Translated by Helen I. Needham. Chicago, IL: Moody, 1969.

Payne, D.F. “Targums.” Pages 1238-39 in The New Bible Dictionary. Edited by J. D. Douglas. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1962.

Rimmer, Harry. Internal Evidence of Inspiration. 7th edition. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1946.

Waltke, Bruce K. “Old Testament Textual Criticism.” Pages 156-86 in Foundations for Biblical Interpretation. Edited by David S. Dockery, Kenneth A. Mathews, and Robert B. Sloan. Nashville, TN: Broadman, 1994.

Wilson, Robert D. A Scientific Investigation of the Old Testament. Revised edition. Revised by Edward J Young. Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1967.

Woods, Clyde. “Can we be Certain of the Text? – Old Testament.” Pages 94-102 in God’s Word for Today’s World: the Biblical Doctrine of Scripture. Don Jackson, Samuel Jones, Cecil May, Jr., and Donald R. Taylor. Kosciusko, MS: Magnolia Bible College, 1986.