Jack P. Lewis, Leadership Questions Confronting the Church (Nashville, TN: Gospel Advocate, 1985), paperback, 111 pages.

Dr. Jack Pearl Lewis (1919–2018) was educated at Abilene Christian University and Sam Houston State Teacher’s College, receiving a PhD. from both Harvard University and Hebrew Union College. Lewis was associated with the Harding Graduate School of Religion (now Harding School of Theology) since it opened in 1958.[1] Lewis’s biblical scholarship, his influence as a teacher, his involvement as a translator of the NIV, his estimation in the academic community, and his love for the Lord’s church earned him a great deal of respect. He has laid much ground for those seeking an understanding of the biblical text and its historical context.

When I was a residential student attending Freed-Hardeman University (Henderson, TN), Lewis’s lectures were always a “must attend” session during the Annual Bible Lectureships. Thanks to my Greek professor, I had a chance to talk with him. When I asked him what an undergraduate Bible major should focus on when preaching and teaching Dr. Lewis said in his understated voice: “be prepared.” Clearly, it was advice he lived by as Dr. Lewis “prepared” himself for the task of providing guidance in the study of God’s word. As a result, he became a scholar’s scholar.

In 1985, Lewis released an anthology of articles from a variety of Christian periodicals and lectureships on critical leadership topics. These articles were collected into a single volume of fifteen chapters, Leadership Questions Confronting the Church.[2] Chapters 4 and 7 are the exceptions, having been serialized word studies now combined here. Each chapter can stand alone as a profitable study on leadership questions, but as a collection, it provides a helpful series of studies.

In the “Foreword,” Dr. Lewis states the reason for the collection: “The reception they received, both from those who criticized and those who applauded, suggested that they would be of use to a wider audience.”[3] The goal of this collection rests in his prayer, “May the Lord help us to find out and to practice his will in matters of leadership as well as in all other matters.”[4]

Well-Researched

The best feature of this compact volume is the wealth of research, analytical thinking, and practical wisdom crystallized on every page. In 111 pages, Dr. Lewis tackles a variety of thorny issues regarding the eldership, the eldership authority-influence debate, leadership without elders, preachers, and their function and authority, and responds to misunderstandings regarding authority (who has it, what kind is it, etc) in a style that is often described as an “economy of words.”

Dr. Lewis places the biblical evidence on display, summarizes the evidence in a few words, and calls attention to complications that often fall upon the church in applying the thrust of a word or passage. There are many instances where Dr. Lewis reveals his heart for the Lord’s church as a church “statesman” (Dr. Lewis would probably prefer Bible student). All these observations seem to be best demonstrated with the following quotation:

Words create the patterns in which men think. Before we divide the church over the implications of a word that does not occur in the Bible in the context with which we are differing from each other, would it not be rational to give thought to the possibility of the need for a more Biblical pattern in which to express ourselves? If we use Biblical terms we might not find ourselves so far apart after all.[5]

Jack P. Lewis, Leadership Questions Confronting the Church (1985)

Dr. Lewis is sensitive to pointing out a perceived or traditional view of leadership that is influenced by denominational tendencies, early Restoration Movement misconceptions, or a lack of preparation to study the Scriptures. He calls on the teaching leaders in the Lord’s church to adequately prepared themselves to understand their function and purpose by properly studying and applying Scripture. Only then will they have a foundation for their ministry.

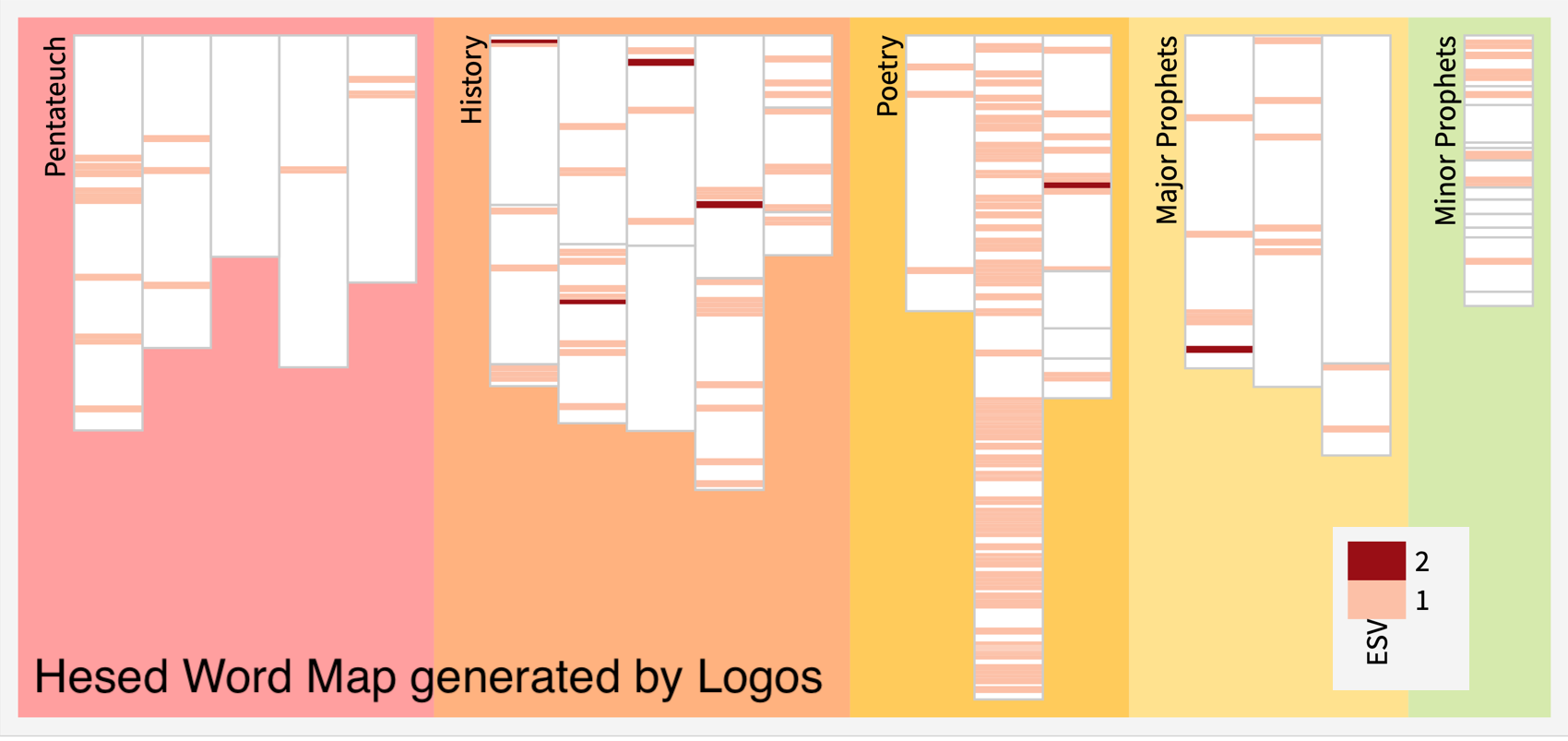

Valuable Word Studies

A second aspect that makes the volume very useful is the word studies on the elders (ch. 4) and on the preacher (ch. 7).[6] The majority of the chapters are brief; however, the section on word studies stand as the bulk of the book. It demonstrates Lewis’s painstaking scholarship and his confidence in the Bible as the source for Biblical research.

While these approaches have their place and invite a wide appeal, Dr. Lewis approaches such topics by delving into the language of the Scriptures reflecting the very principles he calls others to apply:

“You must apply the seat of your pants to a chair for long periods of time.”[7]

In the course of these word studies, Dr. Lewis explores the various terms in all of their cognate and morphological considerations in order to explore their contextual use.

Where some may spurn such a study, Dr. Lewis explores the stewardship necessary to understand what God has said regarding leadership roles in the church. For this very reason, Dr. Lewis encourages his readers,

“As a preacher you need time in your schedule, not directly related to sermon preparation, when you are not available for the telephone […] a time in which you will sharpen up your Greek and Hebrew.”[8]

Why? Lewis explains the responsibility,

“Have you ever thought of the presumption there is in passing yourself off as an interpreter of a book you cannot read?”[9]

His words are a wake-up call to every leader who desires to understand God’s Word and to lead God’s people in the follow-through of obedience.

Slight Limitations and Suggestions

In general, it may be said that Leadership Questions Confronting the Church is quite valuable and provides guidance in particular areas; however, Dr. Lewis only indirectly addresses questions confronting the church with regard to the role of women and the topic of deacons. Dr. Lewis touches on certain elements of the role of women in chapters 1 and 2 but does not address the broader issues. It should be said that Dr. Lewis addresses the positive case of Scripture — what does the Scripture say? — and then proceeds to call upon church leaders to uphold what the Scripture teaches.[10] In both cases, Dr. Lewis concedes his focus is not to exhaustively treat the question of women’s roles in the church.[11]

Regarding the leadership question of deacons, Dr. Lewis pays little direct attention aside from allusions to certain similarities of qualifications with elders or in those distinctive qualifications that separate the two ministries.[12]

In the second place, there are a few modest suggestions that would improve the usefulness of Dr. Lewis’s anthology as a leadership resource. Should a revised or updated edition be considered, an index of Scriptural, Rabbinic, and Ancient Literature references, an original language word listing index, and a topical index would be a welcomed feature of the book. The content is very rich and quickly invites many personal notations and highlights, these suggested indexes would be very welcomed to make this book more useable.

Another suggestion that would require an updated edition is to re-release in two formats, in print and electronically (Mobi, Kindle, Logos, Adobe, etc). This suggestion would bring a very helpful book into the hands of the “e-reader” generation, and such an update would allow perhaps an appendix to include other available material such as his “A Challenge to New Elders.”[13]

Recommendation: High

For its size and for the fact that Leadership Questions Confronting the Church is nearing its 40th anniversary, Dr. Lewis has produced a primer of enduring value for those searching for answers to broad and thorny issues regarding the ministry of elders and preachers. Few books can boast that kind of longevity. The scholarship, the wisdom, the clear thinking, and the leadership to call out observed inconsistencies in brotherhood applications make this small volume a must-read for preachers in training and the veteran, for newly called elders, and elders who have been in the work for some time.

Christian leaders need to sharpen their deliberative skill set, as Dr. Lewis writes, “The most valuable thing about a man is his power of judgment.” The work is well written and there is much to chew on, and aside from the larger specialized word study chapters (4 and 7), this series of articles would benefit every concerned leader and Christian looking for guidance on these leadership topics. Leadership Questions Confronting the Church is more than a mere series of articles, it is a reminder of the importance that church leadership must constantly be undergirded by biblical authority and proper study of the Scriptures.

Endnotes

- Jack P. Lewis, Basic Beliefs (Nashville, TN: 21st Century Christian, 2013), 7.

- Jack P. Lewis, Leadership Questions Confronting the Church (Nashville, TN: Gospel Advocate, 1985).

- Lewis, Leadership Questions, “Foreword.”

- Ibid.

- Lewis, Leadership Questions, 11–12.

- Lewis, Leadership Questions, 13–35, 49–70.

- Lewis, Leadership Questions, 104.

- Lewis, Leadership Questions, 106.

- Ibid.

- In one instance he writes, “It is not the purpose of this paper to discuss the minutia of what women can and cannot scripturally do. It is to call attention to specious reasoning that is being engaged in on a concept that is not in the Greek text at all” (Lewis, Leadership Questions, 8)

- Lewis, Leadership Question, 6, 8. Elsewhere Lewis addresses the matter of Phoebe in “Servants or Deaconesses? Romans 16:1” in Exegesis of Difficult Biblical Passages (1988; repr., Henderson, TN: Hester Publications, no date), 105–09.

- At the time of publication, Dr. Lewis had not addressed New Testament materials regarding deacons of the church. See Annie May Lewis, “Bibliography of the Scholarly Writings of Jack P. Lewis, ” Biblical Interpretation: Principles and Practice – Studies in Honor of Jack Pearl Lewis (ed. F. Furman Kearley et al.; Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 1986), 329-36. An online search on the Restoration Serial Index results in no articles by Lewis on deacons.

- Jack P. Lewis, “A Challenge to New Elders,” Gospel Advocate 143.5 (May 2001): 34-35. Another suggestion would be to include, “Elders’ Wives,” Gospel Advocate 136.12 (Dec 1994): 35.

- Lewis, Leadership Questions, 37