I was recently asked to explore various symbols related to the Christian faith. I have thought about how to share these brief notes. I decided to piece them together here for your consideration. Christians respond diversely to symbols. I am using this word as an action or icon that invites reflection on Jesus and the Christian faith.

There are creedal statements like the Old Roman Symbol (c. 215) called “symbol,” of sample of it reads:

I believe in God, the Father almighty. And in Christ Jesus, his only Son, our Lord, who was born of the Holy Spirit of the virgin Mary, who was crucified under Pontius Pilate and was buried, the third day he rose from the dead. He ascended into heaven, is seated at the right hand of the Father. From there he will come to judge the living and the dead.1

The following symbols have confessional value but they are not as direct as “I believe…” statements.

The Marks of Jesus

Injuries caused by persecution have a way of telling the story of our faith in Jesus. Paul wrote Galatians about a couple of years before AD 50 to Christians entangled in a crisis over the nature of the true Gospel message, likely just before the so-called Jerusalem Council (Acts 15).

Some had clearly been subject to the quick work of certain false teachers imposing a strong retention of Judaistic practices as essential to the faith. Paul dispatches Galatians to undo the corrupting influence of this false gospel by outlining that justification by faith in Christ was the essence of the Law, and always intended to transcend and consummate the Law. This was accomplished on the basis of the promises granted to Abraham, made operative by faith in Christ which is entered into at baptism (Gal 2:15-5:1). This new life in the Spirit provides the rule of life for the Christian (Gal 5:2-16). At the close of this letter, the apostle signs off with what appears to be words of exhaustion:

From now on let no one cause me trouble, for I bear on my body the marks of Jesus. The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with your spirit, brothers. Amen. (Galatians 6:17-18 English Standard Version2)

What is remarkable is that the apostle could claim that he wore on his body “the marks of Jesus” so early in his ministry. Let me unpack this briefly. These marks (stigmata) that Paul bears (bastadzo) on his body are likely scars.3

According to Acts, during Paul’s traditional “first” mission there is one explicit case of physical violence for this early claim (Acts 13-14). There was persecution in which Paul and Barnabas were driven out of Antioch (Acts 13:50). Early in their work in Iconium, mistreatment and stoning were attempted on them by Gentiles and Jews (Acts 14:5). Later, Jews arrived in Iconium from Antioch and stoned Paul, and then they dragged his body out of the city “supposing he was dead” (Acts 14:19). He must have looked convincingly dead-or was-from the stoning when he rose up and continued his mission (Acts 14:20).

So when Paul wrote “I bear on my body the marks [scars] of Jesus” he could literally point to the scars on his body as witnesses of persecution for his service to Jesus. This would only be the beginning of his sufferings, as the Lord Jesus explains that Paul’s calling as a chosen instrument will be accompanied by suffering: “For I will show him how much he must suffer for the sake of my name” (Acts 9:16). Paul words point to that our injuries experienced in the line of Christian duty tell the story of Jesus, his own suffering on the cross, and our faith in him as our resurrected Lord.

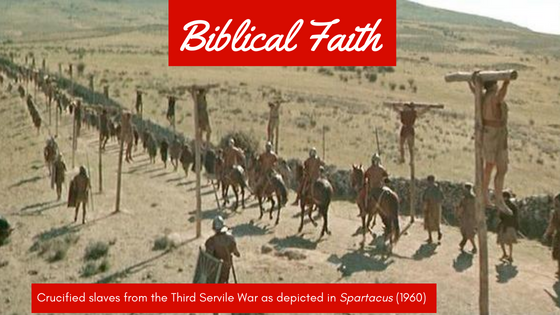

The Cross of Christ

In the Third Servile War (73-71 BC), rebel slaves led by Spartacus lost the war, and of the survivors all six thousand seditious slaves were crucified by General Marcus Licinius Crassus (115-53 BC) along the Appian Way in Italy. There is an irony that the symbol of the Christian faith was the Roman tool to end insurrectionists. It was a symbol of Roman power as they executed enemies of the state in one of the most humiliating public displays of power disparity.

For the executed it was a clear failure of their insurrection, as the impotence of their cause is placed on full display. Crucifixion was to execute and embarrass its victim and to announce the futility of the movement to all its followers and all who would attempt to pick up its torch. Clearly, the Jewish opponents among the leadership in Jerusalem desired to not only execute Jesus but also quell his messianic movement as others before him.

Even in the biblical text, execution by hanging was a shame and a curse:

And if a man has committed a crime punishable by death and he is put to death, and you hang him on a tree, his body shall not remain all night on the tree, but you shall bury him the same day, for a hanged man is cursed by God. You shall not defile your land that the Lord your God is giving you for an inheritance. (Deuteronomy 21:22-23)

It is remarkable that this text is equated with the shame of the cross of Christ. In Galatians, Paul writes, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is written, ‘Cursed is everyone who is hanged on a tree’ ” (Gal 3:13). Peter and the apostles affirmed to the Jewish council that “the God of our fathers raised Jesus, whom you killed by hanging him on a tree” (Acts 5:30). Clearly, the redemptive outcome from the crucifixion of Christ transformed the value of the cross of Christ, and this is seen in Paul’s declaration to the Corinthians: “For I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ and him crucified” (1 Cor 2:2). The cross means the humiliation of Christ, but it also means our redemption by Christ’s substitutionary death. It is to be the source of our boasting, “by which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world” (Gal 6:14).

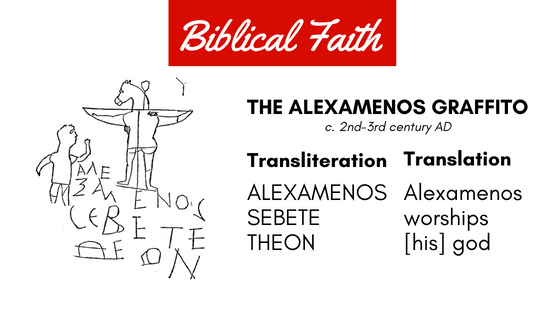

There is ample evidence that Christian persecution began early in the first century, most of it was sporadic rather than systemic. One curious example comes from an anonymous ancient antagonist who carved his aggression against a certain Christian named Alexamenos. This late second century, or early third century, carving is known as the Alexamenos Graffito, and it portrays a crucified man with the head of either a donkey or a horse and wrote around it:

ALEXAMENOS WORSHIPS [HIS?] GOD.4

Even when Christians were publicly shamed in graffiti, Christianity is represented by their “crucified god.” This type of ridicule from the public nevertheless shows a clear connection between the cross and the Christian Way and an early understanding of the divinity of Jesus.

It is possible that the Crucifix (the image of Jesus on the cross) as such emerged around the sixth century as a symbol of Christianity. The cross, however, has been forever paired with the proclamation of the gospel. Today it is in hospitals, as “the hospital” was invented by Christians who opened homes to care for the sick as early as the fourth century. The Red Cross as a benevolent organization uses the symbol of the cross as a symbol of compassion and concern, key beliefs of the Christian faith.

The Jesus Fish <><

The creativity of the ancient Christians is remarkable. Every now and then something of this ancient creativity finds its way back into the hands of the faithful. During the turbulent times of the 60’s and 70’s the fish symbol re-emerged as a cultural symbol of the Christian faith. But how did the fish symbol come to be used by ancient Christians?

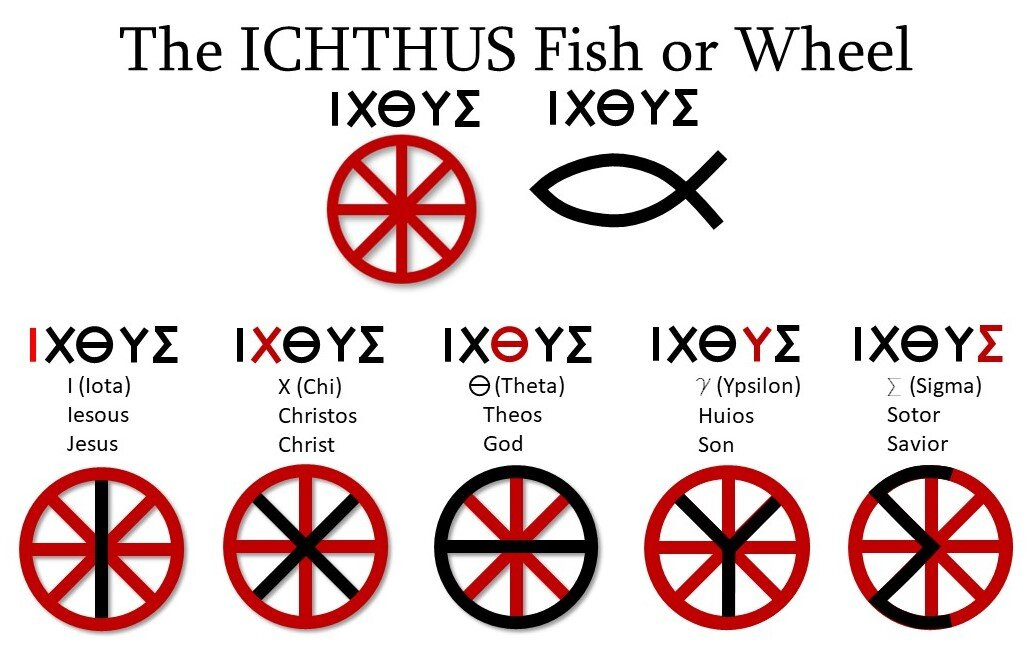

One tradition says it goes back to times of persecution. When Christians would travel and find themselves in the company of strangers, they would draw on the ground an outline of a fish to see if they were among fellow believers.5 It was a symbol that veiled a hidden message: “I believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, the Savior.” The Greek word for fish (ichthus) had become an acronym for the above creedal statement.

Let’s unpack this a little more. Using our English letters to phonetically represent the Greek letters in the fish (ichthus) acronym, we have:

i (iota) = Iesous (Jesus) ch (chai) = Christos (Christ) th (theta) = theos (God) u (upsilon) = huios (son) s (sigma) = Soter (savior)

Literally, it translates to: “Jesus Christ God Son Savior.” Sometimes it was drawn as a fish and other times as a circle with many lines like a pizza.

Today, the Jesus fish is a widely recognizable cultural icon of the Christian faith. It is no longer the hidden message it once was. Friend and foe know it as part of the Christian “branding.” Evolutionists, atheistic skeptics, and ufologists have even made their own mocking versions. Nevertheless, the Jesus fish is an ancient Christian symbol affirming our faith claim that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, the Savior.

Walking After His Pattern

The best image of Christ anyone will meet is the Christian who follows after the example of Jesus in the way they live their life and love their neighbor. In Peter’s letter, the apostle invites us to a life of deep commitment with the following words:

For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, so that you might follow in his steps. (1 Peter 2:21)

The Christians Peter is writing to are experiencing a variety of tensions in their lives with neighbors in their community challenging them, criticizing them, and perhaps even forcing them into public legal situations where they must defend themselves and their new way of life.

Here, Peter calls on the imagery of children learning to write their letters by using a stencil to copy the letters until they can write the letters on their own. In the word “example” (hupogrammon) is found this ancient practice of children learning how to write their letters.6 Jesus is our template, our model, our tracing paper as we learn how to live a life as a servant of Christ.

In this section of his letter (1 Pet 2:21-25), Peter quotes and alludes to the suffering servant passage of Isaiah 53 as describing and outlining how Jesus endured rejection and suffering even to the point of the cross. How Jesus faced the cross, Peter argues, is how Christians ought to face the challenges of the world they live in. In short, his willingness to suffer on the cross becomes our paradigm/model for living. Scot McKnight puts a helpful perspective on this text:

Here is an early Christian interpretation of Christ’s life that is, at the same time, an exercise in the explanation of the essence of the Christian life. This little section, in other words, is a glimpse into a Christian worldview of the first century—a world not at all like our world because of the predominance of suffering in the early church, but a worldview that retains its significance for Christian living.7

Scot McKnight, 1 Peter, NIVAC

As the reasons for being a Christian drift towards matters of “to be better,” “to help others,” “to find community… a family…,” or something one could obtain from a support group or self-help book, the nagging truth of Christian discipleship formed by the paradigm of Jesus and his suffering on the cross for our redemption, the church may never come to realize its primitive spirit of sacrificial consecration prepared to do likewise as the sacrificial sheep of God.

The Christian is redeemed by the suffering Christ, and it is an essential part of the Christian life to endure suffering as we serve the Christ of the gospel we proclaim and live by.

What Symbols Do You Bear?

I hope these short reflections will help you think about how we think about Jesus in our life of faith. Are we marked by sorrow, pain, or harm from following Jesus? If not pray for others who have. Perhaps you have other ways to speak of your faith. Do you glory in his cross? Do you focus on the work of Christ on the cross and what that means for the work of Christ happening in your heart? Take time to meditate on this truth.

Our symbols may need some unpacking, like the Jesus Fish, but perhaps instead of looking at it as a “cheesey” Christian pop icon, you may see it as a meaningful symbol born from persecution for simply being a Christian. Nevertheless, the only symbol of Christ that truly touches the hearts of men is that of a Christian walking in the steps of his suffering servant Jesus.

May God bless you.

Endnotes

- Old Roman Symbol. ↩︎

- All Scripture quotations are taken from the English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway). ↩︎

- J. Louis Martyn, Galatians: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, AYB 33A (New Haven, CT: Yale, 1974), 56. ↩︎

- Jen Rost suggests a broader window of c. 83 to the third century, “Alexamenos Graffito,” worldhistory.org ↩︎

- Elesha Coffman, “What is the Origin of the Christian Fish Symbol?,” Christianity Today (8 Aug 2008) ↩︎

- John H. Bennetch, “Exegetical Studies in 1 Peter,” BSac 99 (1942), 346. ↩︎

- Scot McKnight, 1 Peter, NIVAC (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996), 168. ↩︎