According to the Gospel of John, during the final hours before his betrayal and crucifixion, Jesus spent the final night with his disciples. This begins the “hour” in which Jesus would be glorified (John 12:27–28). The first “teaching act” Jesus provides his disciples is to wash their feet, illustrating that leadership must be service-oriented among them whether Master and Teacher or servant and disciple (John 13:1–20).

Both Jesus and the narrator of the Fourth Gospel introduce a significant feature here: Jesus served all of his disciples by washing their feet, especially Judas whom Jesus already knew would betray him (John 13:11). This general fact Jesus makes a topic of conversation (John 13:17–20, 21–30). Jesus said:

I am not speaking of all of you; I know whom I have chosen. But the Scripture will be fulfilled, ‘He who ate my bread has lifted his heel against me.’ (John 13:18 English Standard Version)[1]

In Christian interpretation, the “Scripture” reference is to Psalm 41:9 as a prophecy of Judas. As with many New Testament quotations of the Old Testament, the use of this passage in reference to Judas’s betrayal of Jesus generates considerable questions. For example, if this scripture applies to Judas, was Psalm 41:9 void of meaning for centuries until the first century AD emergence of Jesus? This seems unlikely. Additionally, in what sense does Judas fulfill (plēroō) this passage? Is it in a typological, duel-fulfillment (telescopic), or primary/secondary fulfillment sense? These types of questions are important, but they are not the primary concern in this paper.[2]

The present brief study was prompted by the connection between Psalm 41:9 and John 13:18. Nevertheless, the most important concern in this paper is to seek to understand Psalm 41 as a unit.

Thus, the primary focus presently is on understanding Psalm 41 from its historical and biblical context (i.e., Hebrew Bible), its structural features (literary genre, organizational form), and its linguistic features. With these items in place, it will help to consider its theology and application. Finally, a consideration on how to best see how Judas’s betrayal of Jesus “fulfills” Psalm 41:9.

Historical Context

C. Hassell Bullock mentions the great dilemma of studying the historical context of any given psalm and stresses that to obtain a solid footing for explaining the context one must examine the superscriptions and content of the psalm.[3]

Edward Tesh and Walter Zorn observe that perhaps no other psalm rivals Psalm 41 in terms of providing the original setting and significance.[4] They evaluate six possible explanations and conclude that the psalm was probably borne out of a dire situation and was consequently a lament, in which the psalmist appeals for healing. From this dire circumstance, the psalm eventually was incorporated into the liturgy of the temple worship.[5] Other scholars also recognize the “lament” nature of the psalm as informative to understanding the original historical context (Carroll Stuhlmeuller, Peter C. Craigie, Robert G. Bratcher and William D. Reyburn).[6] The internal evidence, then, points to a historical context that generated a lament.

Peter Craigie represents those who argue that the Psalm must be understood in its liturgical use for the sick of Israel, instead of a personal historical context.[7] Likewise, Charles A. Briggs argued that the psalm is national in scope, not individual, because of an emphasis upon God blessing those in the land during post-exilic times (Psa 41:2).[8] The psalm proper begins:

"Blessed is the one who considers the poor! In the day of trouble the Lord delivers him; the LORD protects him and keeps him alive; he is called blessed in the land; you do not give him up to the will of his enemies." (Psalm 41:1–2).

Canonically, the psalm is a communal outcry, and this then speaks to its shaping context. This conclusion seems to be weakened by the fact that there is still an earlier setting that precedes its Hebrew liturgical use. This amounts to a debate between the later canonical use of Psalm 41 with its initial authorial intent.

The tradition contained in the subscription may provide help in understanding the original historical context. The subscription is ancient but it is not likely to be as old as the psalm. It minimally points to what the ancients believed about this psalm. It may help understand the initial authorial intent of Psalm 41 by providing an assumption about the personal emphases throughout the psalm and the psalmist’s dependence upon God. The subscription of Psalm 41 reads: “To the Choirmaster. A psalm of David.” The psalm is Davidic by tradition. Internally, there is nothing inherent in the psalm that would dismiss it as being Davidic.

Unfortunately, some have noted that the translation of the ascription “of David” (le dwd) could be regarded as a dedication “to David.”[9] In addition to versional evidence offered to support the translation for the phrase as “of David,” similar wording can be demonstrated from the Hebrew canon to express authorship.[10] To illustrate, consider one example from Habakkuk:

A prayer of Habakkuk the prophet, according to Shigionoth. O Lord, I have heard the report of you, and your work, O Lord, do I fear. In the midst of the years revive it; in the midst of the years make it known; in wrath remember mercy. (Hab 3:1–2)

This is not a prayer dedicated to Habakkuk, but a prayer of the prophet, as in by the prophet. Despite later reconstructions of redaction and editorial work theories in the canonical shaping of Psalter, it seems reasonable that “to David” in the subscription is a claim of authorship. If there is no need to question Davidic authorship, then the traditional attributions may be considered accurate, and therefore be a line of argumentation against Briggs’ post-exilic interpretation of Psalm 41:2.[11]

The internal evidence, then, is supportive of a time in King David’s lifetime in which he experienced betrayal and treachery by someone close to him, and the presence and faithfulness of his God to vindicate him. This is assumed here to be during his reign in the 10th century BC. Psalm 41 may have been collated afresh in later editions of the Psalter for liturgical or national use, but these developments are secondary contexts.

Literary Form

Psalm 41 is generally regarded as a lament. Its historical context makes it more likely it was an individual lament. Laments are not simply mere prayers of pain. Laments often contours such as an outcry of pain or distress, a declaration of faith based upon some past action of God, lessons learned about God, and a statement of praise. In that sense, a lament can offer insight into a past tragedy in which the lamenter cries out to God and then contains a record of the Lord’s vindication.

For reasons like this, an alternative form for Psalm 41 is what Willem A. Van Germeren calls a “thanksgiving of the individual.”[12] If it is to be considered as a thanksgiving work, then there should be words of praise, some description of God’s gracious action, lessons learned about God, and some form of a conclusion extolling God. It is true the psalm begins with what may be read as thanksgiving for the one who considers the poor for the Lord will deliver him. But while there is certainly an undertow of gratitude throughout the psalm, there is the consistent plea for assistance, deliverance, and an appeal to God’s grace that saturates the psalm. The evidence for lament is stronger than the theme of thanksgiving.

It has also been suggested that Psalm 41 could overlap with the wisdom psalm literary form. Instead of the distressing opening lines of Psalm 22:1 (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”) or Psalm 51:1 (“Have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love”s 51:1”), Psalm 41 begins with a proverbial statement.[13] observe:

“Blessed is the one who considers the poor, in the day of trouble the Lord delivers him.” (Psalm 41:1)

However, the phrase “blessed” is used throughout the Psalms and does not require proverbial emphases. While it could be argued that Psalm 41 does not begin with the type of traditional outcry associated with lament, the wisdom genre does not carry the burden of how the psalmist describes his enemies as conspiring against him:

My enemies say of me in malice, “When will he die, and his name perish?” And when one comes to see me, he utters empty words, while his heart gathers iniquity; when he goes out, he tells it abroad. All who hate me whisper together about me; they imagine the worst for me. They say, “A deadly thing is poured out on him; he will not rise again from where he lies.” Even my close friend in whom I trusted, who ate my bread, has lifted his heel against me. But you, O Lord, be gracious to me, and raise me up, that I may repay them! (Psalm 41:5-10)

Wisdom provides the “how to” knowledge or the “beware” knowledge, the psalmist is decrying his situation.

The psalm begins with a focus on the individual and the Lord’s care of “he who considers the poor.” In a Spanish translation, the Hebrew word dal is translated as “el debil” (Santa Biblia: Nueva Version Internacional), meaning those who are weak. It seems essential to the lament of the psalm that the weak is the psalmist and not necessarily someone about whom the psalmist is reflecting about.

Structure

While this paper will not address the complexities of the original Hebrew text,[14] it is clear that the psalm may be given a variety of outlines depending on how the parallelism is viewed. Not all scholars seem to agree on the arrangement even if they have the same number of structural divisions. For example, the late Hugo McCord (1911–2004) sets the psalm into four stichs in his translation of the Psalms: 41:1–3, 4–6, 7–9, 10–12, and 13.[15] Tesh and Zorn divide the psalm into four different stichs: 1–4, 5–9, 10–12, and 13.[16]

I offer a personal outline for the psalm suggested: 1–3, 4–8, 9–12, and 13.

Psalm 41:1–3: Blessed is the one who considers the poor! In the day of trouble the Lord delivers him; the LORD protects him and keeps him alive; he is called blessed in the land; you do not give him up to the will of his enemies. The LORD sustains him on his sickbed; in his illness you restore him to full health. Psalm 41:4–8: As for me, I said, “O LORD, be gracious to me heal me, for I have sinned against you!” My enemies say of me in malice, “When will he die, and his name perish?” And when one comes to see me, he utters empty words, while his heart gathers iniquity; when he goes out, he tells it abroad. All who hate me whisper together about me; they imagine the worst for me. They say, “A deadly thing is poured out on him; he will not rise again from where he lies.” Psalm 9–12: Even my close friend in whom I trusted, who ate my bread, has lifted his heel against me. But you, O Lord, be gracious to me, and raise me up, that I may repay them! By this I know that you delight in me: my enemy will not shout in triumph over me. But you have upheld me because of my integrity, and set me in your presence forever. Psalm 13: Blessed be the LORD, the God of Israel, from everlasting to everlasting! Amen and Amen.

The groupings seem to fit a thematic development. In verses 1–3, David demonstrates a balancing of the blessed environment of the one who considers the poor with the strength and sustaining power of God. Then, in verses 4–8, David describes the plight he finds himself in. While David seems to be in poor health and under spiritual duress and therefore vulnerable, his enemies reveal themselves as ambitious traitors to the crown. In verses 9–12, the case intensifies as David laments the fact that he has become so isolated that “even” his close friend betrays him. Admit the tension the Lord is appealed to for help so that the psalmist’s suffering may be avenged by the Lord. This would be all the vindication he would need.

Interestingly, the doxology of verse 13 is typically set to stand by itself perhaps as an inclusio. George Knight observes that the psalm begins with “blessed be the man” it ends with “blessed be the Lord.”[17] There is certainly an understood purpose behind this inclusio. Some speculate this verse was added by a later editor or compiler.[18] On Hebrew parallelism, it has been argued that verse 13 does not seem to formally echo or balance with verse 12.[19] Additionally, the language in Psalm 41:13 is remarkably similar to Psalm 106:48 and functions similarly as a formal doxological break between the two books. Psalm 41 closes Book I and Psalm 106 closes Book IV with the same doxology, with an expanded doxology in Psalm 106. However one accounts for verse 13, it is structurally integral to the Psalter.

Imagery

Imagery is an important aspect of Hebrew poetry. Imagery conveys messages and nuances and sometimes brings our emotions. In the Hebrew poetry of the Psalms, the poet expresses truths with images being the channel. Consider a minor sample of some of the imagery concerning God, the psalmist, and the psalmist’s enemy.

Psalm 41:3 refers to the parallel concept of the Lord who strengthens the sick man “on his bed of illness” and “sustain him on his sickbed.” The picture is graphic and is one of physical restoration, which may refer both to spiritual or real renewal.

Psalm 41:6 discusses, from the vantage point of the psalmist, his enemy. His enemy’s “heart gathers iniquity to itself; when he goes out, he tells it.” The psalmist personifies the mind of an evil man and depicts it in the act of gathering iniquity as a person may gather fruits or clothing. Man’s heart is given to iniquity, so much that he self-references is own sinfulness. The enemy of the psalmist is consequently even more devious and methodical.

In Psalm 41:9 the description of the kind of enemy the Psalmist endures is one that is a close associate, one whom he trusted. Trust and eating bread are synonymous phrases in this context, demonstrating the use of parallelism. But the synonym moves on to climatic, where the enemy goes from trusted friend to outright betrayer.

Biblical Context

As previously mentioned in the introduction, from a Christian reading of the Bible, Psalm 41 is associated with Judas Iscariot since John narrates that Jesus declared Judas’ betrayal as a fulfillment of Psalm 41:9. Sometimes the Christ-Judas relationship overshadows David’s own reason for writing the Psalm, his Sitz en Leiben (life’s setting). On the assumption of Davidic authorship of Psalm 41, are there any points in the life of David that can corroborate with the details of the psalm?

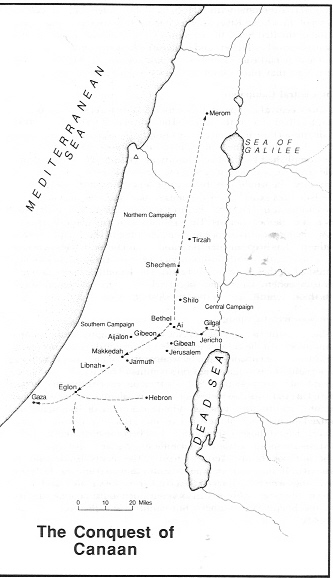

According to Briggs, the traditional Sitz en Leiben of the betrayal and sheer disadvantage displayed in Psalm 41 is that of David’s encounters with Ahithophel of Gilo, his former counselor on the side of his usurping son Absalom (2 Sam 15:1–17:29).[20] It is important to recall that one of the difficulties aligning the setting of the Psalms with the life of David is that not everything was recorded for posterity. Additionally, the narrative language may not always align with the emotional nature of poetry. So, despite the traditional election of Ahithophel (Psa 41:9), it is merely a traditional reading. Consequently, the betrayal by Absalom and Ahithophel may not be what David had intended.

Nevertheless, it is worth considering the relationship between Ahithophel and David. Ahithophel was once a trusted counselor of David (2 Sam 15:31, 34). Ahithophel’s legacy is summed up in 2 Samuel 23:34 as one of David’s mighty men, and in two verses in 1 Chronicles 27:33–34, he “was the king’s counselor… [and] was succeeded by Jehoiada the son of Benaiah, and Abiathar.” He was a man in David’s inner inner circle.

Ahithophel was “David’s counselor” who was successfully courted by David’s embittered son Absalom to overthrow his father as king of Israel in a coup d’é·tat (2 Sam 15:1–12). The tragedy is that his counsel was esteemed “as if one consulted the word of God” (2 Sam 16:23), so his complicity in the conspiracy to overthrow David cut deep (2 Sam 15:31). David, now living on the run and vulnerable, prays to the Lord for the undoing of Ahithophel. Although there is no explicit claim that the Lord rose up Hushai the Archite, this “friend” of David serves as a counter-intelligence spy and undermines confidence in Ahithophel’s military plans against David (2 Sam 15:32–37; 16:15–17:22).

Without explanation, the end of Ahithophel is revealed:

When Ahithophel saw that his counsel was not followed, he saddled his donkey and went off home to his own city. He set his house in order and hanged himself, and he died and was buried in the tomb of his father. (2 Samuel 17:23)

Is this specifically what David meant when he lamented in faith?

Even my close friend in whom I trusted, who ate my bread, has lifted his heel against me. But you, O Lord, be gracious to me, and raise me up, that I may repay them! By this I know that you delight in me: my enemy will not shout in triumph over me. But you have upheld me because of my integrity, and set me in your presence forever. (Psalm 41:9-12)

It is hard to dismiss it even if there is not a clear explicit connection.

Nine hundred years later in the New Testament, the Lord Jesus affirms that this is a reference to Judas (John 13:18). It seems that while David through the Spirit referred to his own situation–whatever it was, the Spirit hid within it a prophecy of betrayal concerning the coming Davidic Messiah likewise from deep within the inner circle. For this reason, Jesus could legitimately claim the Apostle Judas–trusted with the office of an Apostle and keeper of the group’s finances (Luke 6:12–16; John 12:6)–as the fulfillment of this Messianic prophecy. Just as in the case of Ahithophel, no clear motive is ever given for the betrayal of Jesus by Judas.

Theology

The theology of Psalm 41 is connected together by three internal figures: David, David’s God, and David’s enemies. David wrote a lament prayer to his God, who sees both his sinfulness and the injustice as he suffers at the hands of his own enemies, and repeatedly asks God for his gracious deliverance and vindication.

First, David’s lament calls on God’s people to learn the nerve-wracking truth that faithfulness to God will not always protect from the treachery and betrayal of those considered to be allies and members of one’s inner circle. David’s focus on the Lord provides a pathway for making the most important thing the priority: David knows his fellowship with God is unimpeded by his trials. David knows:

the Lord protects him and keeps him alive; he is called blessed in the land; you do not give him up to the will of his enemies (Psalm 41:2)

Second, the powerful king seems to have gone through an illness or some demonstration of weakness which emboldened his enemies to come into the light in anticipation of his collapse or death. David sees his inner court filled with two-faced loyalists, who secretly have grown disloyal to him waiting for the right moment to reveal themselves and exploit his weakness. If the story of David teaches one crucial theological truth it is that God’s anointed will suffer unjustly.

Third, God will vindicate the innocent and the compassionate. David’s ethical and moral life was turbulent. His moral lows are ethically grotesque while his spiritual highs show a deep conviction in aligning himself on the side of the Lord. David was fully aware of his sin but knew the God he served hated injustice and would help those who were poor, or of weak stature. There is comfort in knowing that even though a person may be so weak morally, spiritually, financially, or in health, God desires their protection and care. God will vindicate the taken advantage of.

Application

The message of Psalm 41 is a message for the ages. Many have had friends turn on them, and deliver a heart-piercing stab which only few can do. Intimate relationships can sometimes be vehicles for some to achieve what they want at the expense of those whom they hurt and abuse. We must have the confidence of the psalmist and take refuge in the Lord. The lament provides the language to speak to the Lord in prayer. The psalm calls on the saints to lean into the tragedies surrounding them in faith in the confidence that the Lord is not far from them.

Endnotes

- Unless otherwise noted all Scripture quotations are from the English Standard Version of The Holy Bible (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2001).

- While this sidesteps these important questions, prophecy and fulfillment are not the focus of this paper. In short, however, my conclusion is that while it is hard to determine the sense in which Jesus used plēroō, it seems likely he used it in a typological sense of fulfillment: as David the anointed king of Israel experienced betrayal in his kingdom, so too, the anticipated Davidic Messiah would be betrayed.

- C. Hassell Bullock, An Introduction to the Old Testament Poetical Books, revised ed. (Chicago: Moody, 1988), 125.

- S. Edward Tesh and Walter D. Zorn, Psalms (Joplin, MO: College Press, 1999), 1:306.

- Tesh and Zorn, Psalms, 1:309.

- Carroll Stuhlmeuller, Psalms (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 1983), 1:221; Peter C. Craigie, Psalms 1-50 (Waco, TX: Word, 1985), 321; Robert G. Bratcher and William D. Reyburn, A Handbook on the Psalms (New York: United Bible Society, 1991), 391.

- Craigie, Psalms 1-50, 319.

- Charles Augustus Briggs and Emilie Grace Briggs, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, ), 1:361.

- Raymond B. Dillard and Tremper Longman, III, An Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994), 215–17.

- George A. F. Knight, Psalms (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1982), 1:8; Dillard and Longman, III, An Introduction, 216.

- Andrew E. Hill and John H. Walton, A Survey of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1991), 274–75; Briggs and Briggs, Book of Psalms, 1:361.

- Willem A. Van Germeren, “Psalms” in Expository Bible Commentary, edited by Frank E. Gaebelien (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1991): 5:325.

- Craigie, Psalms 1-50, 320.

- As this paper is primarily an examination of the English text, linguistic concerns as the following will not be explored: W. O. E. Oesterley discusses the abruptness that is characteristic of this psalm and the natural flow of poetic realism which “shows how very human the psalmists were,” he explains however, that the “text has undergone some corruption, and in one or two cases emendation is difficult and uncertain.” See, W. E. O. Oesterley, The Psalms: Translated with Text-Critical and Exegetical Notes, 4th ed. (London: SPCK, 1953), 1:238.

- Hugo McCord, The Everlasting Gospel: Plus Genesis, the Psalms, and the Proverbs, 4th ed. (Henderson, TN: Freed-Hardeman UP, 2000). Granted, McCord did not provide a stylized rendering of the Hebrew poetry, but he did set them in connected paragraphs.

- Tesh and Zorn, Psalms, 1:308–13; Stuhlmeuller, Psalms, 1:220–21.

- Knight, Psalms, 199.

- Craigie, Psalms, 320; Tesh and Zorn, Psalms, 1:312.

- Stuhlmeuller, Psalms, 1:223; W. Oesterley, The Psalms, 1:240.

- Briggs and Briggs, Book of Psalms,1:361.

Works Cited

Bratcher, Robert G., and William D. Reyburn. A Handbook on the Psalms. New York: United Bible Society, 1991.

Briggs, Charles Augustus, and Emilie Grace Briggs. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Vol. 1. International Critical Commentary. Edinburgh: Clark,

Bullock, C. Hassell. An Introduction to the Old Testament Poetical Books. Rev. ed. Chicago: Moody, 1988.

Craigie, Peter C. Psalms 1-50. Word Biblical Commentary. Vol. 19. Gen. eds. David A. Hubbard and Glenn W. Barker. Waco, TX: Word, .

Dillard, Raymond B, and Tremper Longman, III. An Introduction to the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1994.

Hill, Andrew E., and John H. Walton. A Survey of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1991.

Knight, George A.F. Psalms. Vol. 1. Daily Study Bible: Old Testament. Gen. ed. John C.L. Gibson. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1982.

McCord, Hugo. The Everlasting Gospel: Plus Genesis, the Psalms, and the Proverbs. 4th ed. Henderson, TN: Freed-Hardeman UP, 2000.

Oesterley, W. E. O. The Psalms: Translated with Text-Critical and Exegetical Notes. 4th ed. London: SPCK, 1953.

Stuhlmeuller, Carroll. Psalms. Vol. 1. Old Testament Message. Vol. 21. Eds. Carroll Stuhlmeuller and Martine McNamara. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 1983.

Tesh, S. Edward, and Walter D. Zorn. Psalms. Vol. 1. College Press NIV Commentary. Eds. Terry Briley and Paul J. Kissling. Joplin, MO: College, 1999.

VanGermeren, Willem A. “Psalms.” Expository Bible Commentary. Vol. 5. Gen. ed. Frank E. Gaebelein. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1991.